Long before Texas became a land of ranches, railroads, and cities, it was home to a vibrant mosaic of Native peoples. From the piney woods of the northeast to the desert mountains of the west, each region supported its own communities—farmers, hunters, traders, and coastal fishers—who shaped the land long before European explorers arrived.

These were the original peoples of Texas: the first inhabitants who laid the cultural foundation of the state we know today. Though many were displaced or dispersed, their descendants and legacies continue to influence Texas history and identity.

Texas at a Glance: Lands and Regions

The state’s vast size created diverse environments for Native life.

- East Texas offered forests, fertile rivers, and natural lakes.

- Central and North Texas featured rolling plains and bison ranges.

- South and West Texas provided arid deserts, canyons, and borderlands connected to Mexico.

- The Gulf Coast supplied fish, oysters, and sheltering bays for maritime tribes.

These regions were tied together by rivers—the Colorado, Brazos, Trinity, Red, and Rio Grande—serving as highways for travel and trade among the tribes.

The Tribes of Texas

Caddo

Living in the rich woodlands of northeast Texas, the Caddo built large, organized towns with earthen temple mounds and cultivated corn, beans, and squash. Renowned as farmers, potters, and traders, they connected to distant peoples through intricate trade networks.

The Caddo greeted early European explorers with diplomacy, giving Texas its name—derived from Taysha, meaning “friend.” Today, the Caddo Nation continues in Oklahoma, preserving their language and traditions.

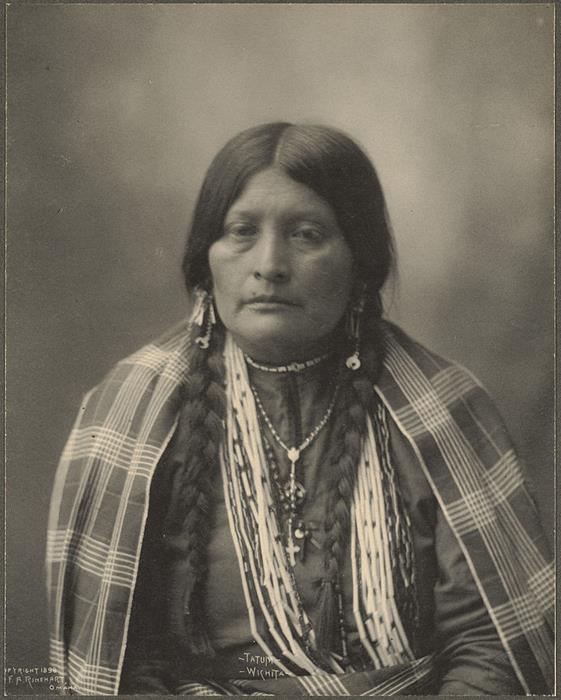

Wichita

The Wichita lived in north-central Texas, between the Red and Brazos Rivers. They grew crops in river valleys and hunted bison on the plains, blending agriculture with mobility. Known for the tattoos that earned them the nickname “Raccoon-eyed People,” they traded with the Caddo and Plains tribes.

By the 1800s, they relocated northward; their descendants are part of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes in Oklahoma.

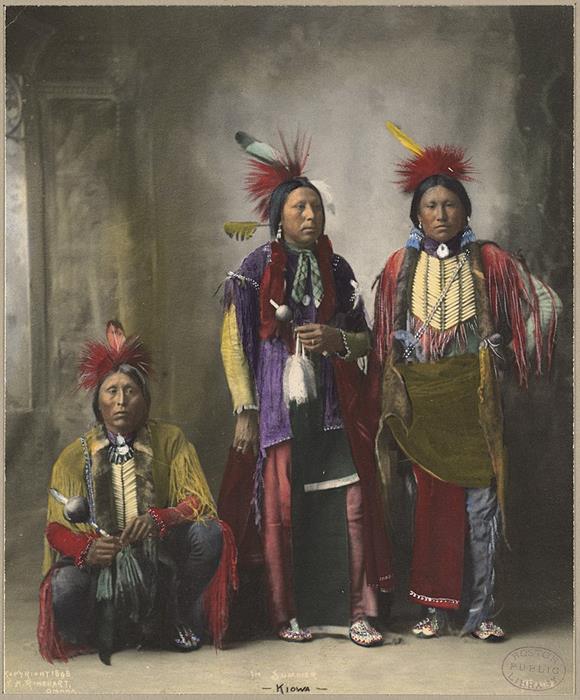

Kiowa

In the Texas Panhandle, the Kiowa thrived as nomadic buffalo hunters. They were exceptional horsemen and artists, famous for detailed ledger drawings that recorded their histories. Often allied with the Comanche, they dominated the southern plains until military defeat in the late 1800s.

Today, the Kiowa Tribe maintains its cultural heritage in Oklahoma.

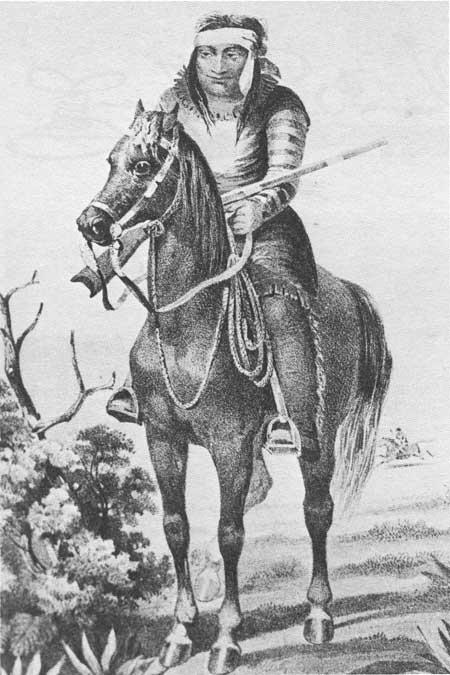

Comanche

The Comanche, known as the “Lords of the Plains,” controlled a vast territory called Comanchería, stretching across central and western Texas. Masters of horsemanship, they became one of the most powerful Native nations in North America.

They traded, raided, and defended their lands fiercely. By the late 1800s, U.S. military campaigns forced their removal to reservations, but the Comanche Nation continues today, proud of their legacy as skilled warriors and traders.

Tigua (Ysleta del Sur Pueblo)

The Tigua, or Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, are descendants of Pueblo people who fled south to Texas after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. They founded Ysleta del Sur Pueblo near El Paso, maintaining traditional farming and irrigation practices.

Despite centuries of challenges, the Tigua remain a federally recognized tribe, operating cultural and educational programs that preserve their Puebloan heritage.

Jumano

Occupying the Trans-Pecos region and the Concho and Rio Grande valleys, the Jumano were known as traders and intermediaries between Plains and Pueblo peoples. They lived in both permanent villages and mobile camps, adapting to desert and river environments. Spanish explorers often described them as friendly guides.

Over time, disease and migration scattered the Jumano, but their legacy survives through descendant communities and archaeological findings in West Texas.

Concho

The Concho lived near the Río Conchos and Río Grande, especially around La Junta de los Ríos near present-day Presidio. They farmed fertile river valleys, fished, and traded with neighbors such as the Jumano and La Junta Indians.

Spanish colonization disrupted their settlements, leading to decline and assimilation into Mexican and Apache populations.

Lipan Apache

The Lipan Apache roamed South and West Texas, from the Edwards Plateau to the Rio Grande. They were skilled horsemen who hunted buffalo and deer while gathering desert plants. Fiercely independent, the Lipan resisted colonization but also formed shifting alliances with Spanish, Mexican, and Texan forces.

Though many were later absorbed into the Mescalero Apache or relocated to Mexico, Lipan Apache descendants remain active in Texas today, preserving their heritage through cultural revival.

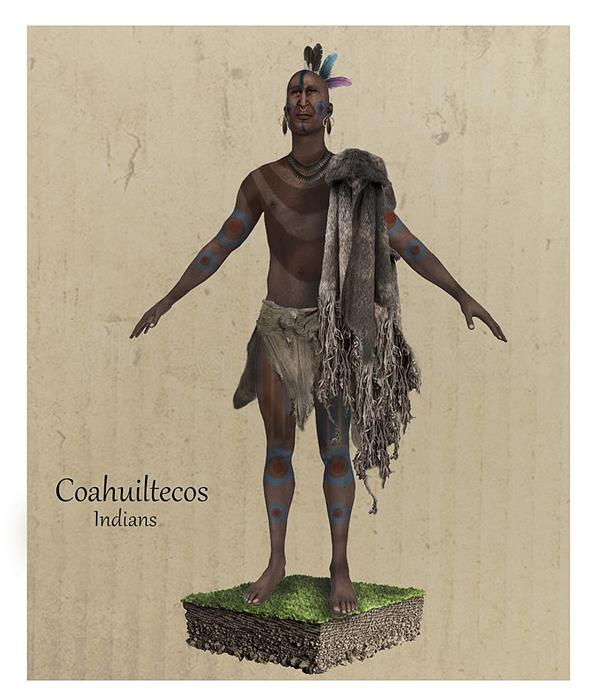

Coahuiltecan

In South Texas and northern Mexico, numerous small bands collectively known as Coahuiltecan lived as hunters and gatherers. They survived in a harsh environment by foraging mesquite beans, prickly pear, and roots.

Many were later drawn into Spanish missions in San Antonio and along the coast, where they merged into new communities. Their descendants still live in the region, keeping alive ancient traditions of resilience and adaptation.

Karankawa

Along the Texas Gulf Coast, the Karankawa were expert canoe builders and fishermen. They lived in small, mobile bands, moving seasonally between the bays and prairies. Though early explorers often misrepresented them as violent, modern historians recognize their sophistication in adapting to the coastal environment.

While their numbers dwindled in the 1800s, Karankawa descendants are active today, reclaiming their history and restoring their name.

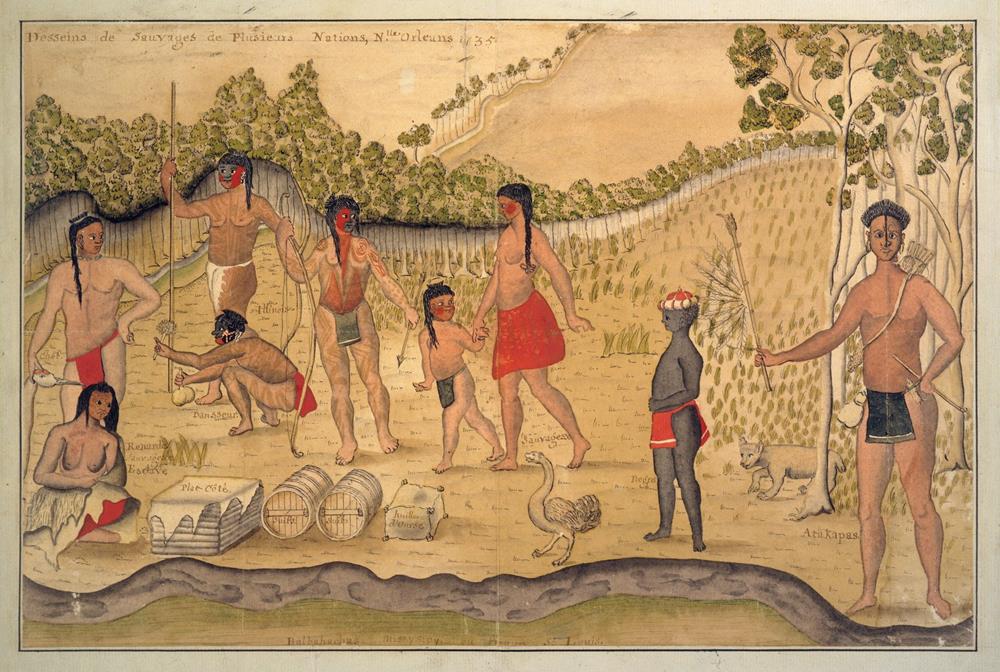

Atakapa (Ishak)

The Atakapa, or Ishak (“the people”), lived in southeast Texas and southwest Louisiana, thriving in the wetlands and bayous. They fished, hunted, and gathered along the Trinity and Sabine Rivers. The Akokisa, a Texas band, lived near Galveston Bay.

Disease and displacement during European colonization led to their decline, but their descendants in both states continue efforts to preserve Atakapa language and heritage.

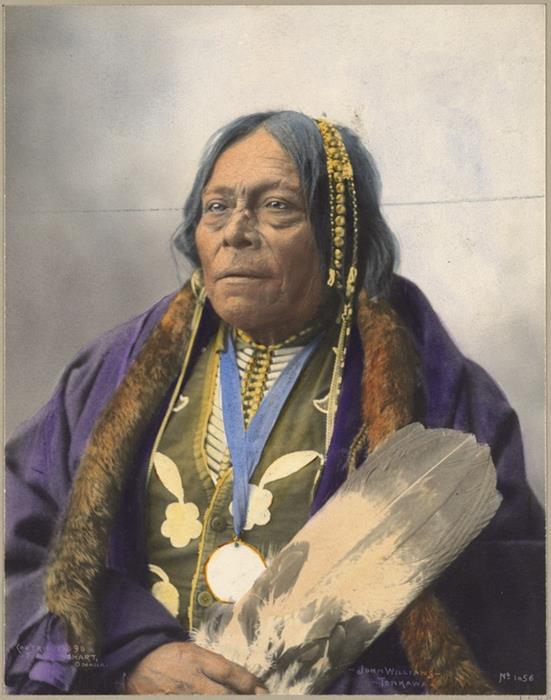

Tonkawa

The Tonkawa lived across central Texas, known for their mobility, hunting skills, and adaptability. They often allied with Texan and U.S. forces during the 1800s, serving as scouts and interpreters.

After years of conflict and forced relocation, the Tonkawa Tribe of Oklahoma remains active, maintaining cultural traditions through annual gatherings and language preservation programs.

Shared Threads and Key Differences

Despite their differences, Texas tribes shared deep ties to their environments. Caddo and Wichita communities farmed river bottoms, building towns, storehouses, and trade hubs, while Comanche and Kiowa perfected fast, mobile lifeways centered on the horse and bison.

Along the coast, Karankawa and Atakapa (Ishak) traveled by dugout canoe and timed camps to tides and seasons. In the west, Jumano and Concho peoples clustered near springs and river confluences, balancing gardening with hunting, fishing, and wide-ranging trade.

Tigua (Ysleta del Sur Pueblo) sustained Pueblo irrigation traditions, while Coahuiltecan bands adapted to arid South Texas through foraging, small-game hunting, and seasonal movement. Lipan Apache bands blended mounted hunting, gathering, and cross-border exchange, shifting routes as pressures changed.

Trade networks connected distant nations through salt, stone, pottery, hides, shells, and later horses. After the 1600s, horses expanded mobility and warfare, guns altered diplomacy and defense, and epidemics like smallpox and measles devastated populations and reshaped alliances.

Missions, Frontiers, and Change

Spanish missions and presidios introduced new religions, crops, and labor systems. Some groups entered missions—such as Coahuiltecan bands in San Antonio and Akokisa near Galveston/Trinity—while others, like many Lipan Apache and Comanche, resisted sustained settlement and negotiated from the open plains.

Frontier pressures multiplied as French trade, then Mexican ranching, and later Texian and U.S. expansion advanced across tribal homelands. Alliances shifted—Comanche–Kiowa pacts, Tonkawa service as scouts, Jumano ties with Spaniards—while conflicts, slaving raids, and disease spurred migration and consolidation.

By the 1800s, removals and warfare pushed many peoples toward reservations in Indian Territory or into New Mexico and northern Mexico. Tigua secured a community at Ysleta del Sur, Caddo, Wichita, Kiowa, Comanche, and Tonkawa endured removal but persist as organized nations, and Lipan Apache descendants remain across Texas and the borderlands.

Most Native nations faced dispossession, assimilation policies, and near-extinction in records, yet their presence endures in living languages, ceremonies, museums, cultural centers, and descendant organizations. Today, their stories shape how Texans understand the land—and how the land remembers them.

The Tribes Today

Many of Texas’s original tribes live on in Oklahoma, New Mexico, and northern Mexico, while several—like the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (Tigua) and Lipan Apache descendants—remain in Texas. Their communities continue to preserve ceremonies, languages, and ancestral lands through cultural centers, education programs, and annual events.

Learning their stories helps Texans understand that the state’s history didn’t begin with European colonization—it began with thousands of years of Indigenous life, culture, and innovation.

Conclusion

The original peoples of Texas built the foundations of this land—its trails, villages, trade routes, and even its name. From the Caddo in the piney woods to the Karankawa on the coast and the Jumano in the desert valleys, their stories reveal the true depth of Texas’s past.

To understand Texas is to remember the nations who first called it home, and to honor those whose descendants keep that heritage alive today.