The Tonkawa tribe played a pivotal role in the early history of Texas as adaptable hunters, skilled scouts, and enduring survivors of cultural upheaval. Although they were often overshadowed by larger and more aggressive tribes like the Comanche and Apache, the Tonkawa maintained a deep connection to the hills, rivers, and plains of Central Texas for centuries.

Their story is not simply one of loss—it is one of remarkable resilience, adaptation, and survival in the face of tremendous change brought by colonialism, warfare, and forced displacement.

Who the Tonkawa Were

The name “Tonkawa” was given by neighboring tribes and is believed to mean “they all stay together” or “the people who stay.” However, the Tonkawa referred to themselves as Tickanwa•tic, which translates to “the most human people,” reflecting their belief in their cultural identity and spiritual purpose. This name also hints at the deeply communal nature of their society.

Their language, often called Tonkawan, is considered a linguistic isolate—meaning it is not clearly related to any other known language family. Spanish missionaries in the 1700s attempted to record and translate parts of the Tonkawa language, though only fragments survive today.

Efforts by the modern Tonkawa Tribe in Oklahoma have led to language classes and documentation projects to reclaim this piece of their heritage.

Where the Tonkawa Lived in Texas

The Tonkawa homeland extended across a vast region of Central and South-Central Texas. They lived along the Edwards Plateau, the riparian valleys of the Brazos, San Gabriel, and Colorado Rivers, and the rolling terrain of the Texas Hill Country. This strategic placement gave them access to bison herds on the plains to the north and abundant plant resources to the south.

Archaeological findings in present-day Travis, Bell, Williamson, and Bastrop counties show traces of Tonkawa campsites, including stone tools and fire pits used to roast mesquite beans and cactus pads. Their seasonal movement often followed the ripening cycles of prickly pear cactus (a staple food source) and the migration of game animals.

As European and Anglo-American settlers spread into Texas in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Tonkawa were gradually pushed from their homelands. They were eventually relocated to reservations along the Brazos and later removed entirely from Texas, despite their long history of cooperation with settlers and soldiers.

Everyday Life on the Plains and Plateaus

The Tonkawa lived as semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, traveling in small family bands of 15 to 30 people. They constructed temporary shelters made of brush, grass, and animal hides, known as wickiups, which could be quickly assembled or taken down as the seasons changed.

The Tonkawa diet was diverse and well-adapted to the Central Texas environment. They were formidable hunters of buffalo, deer, rabbit, turkey, and quail. When bison herds became scarce due to competition from the Comanche and overhunting by settlers, they shifted their diet toward gathered foods such as:

- Prickly pear cactus (both the pads and fruit were eaten)

- Mesquite beans, ground into nutritious flour

- Pecans, acorns, and wild plums

- Roots and tubers

- Fish and freshwater mussels from Texas rivers

After the introduction of the horse in the 1700s, the Tonkawa’s hunting efficiency greatly increased. Horses also became symbols of wealth and status, enabling them to travel longer distances, trade with distant tribes, and conduct defensive raids.

Social Organization and Culture

The Tonkawa people did not form a single centralized nation. Instead, they lived in bands connected through kinship. Each band had a chief or headman, chosen for his wisdom, generosity, and bravery. Decisions were made collectively, often through council meetings where elders and respected warriors contributed to discussions.

The Tonkawa were known for:

- Elaborate body painting and tattoos, often applied before hunts or battles

- Storytelling traditions that passed down history orally

- Sign language, which they used for trade and diplomacy with neighboring tribes

- Music and dance, especially during ceremonies and seasonal celebrations

The mitote, a major Tonkawa ceremony, involved dancing around a central fire, singing songs to the Creator, and communal feasting. These ceremonies reinforced community bonds and honored the spirits of animals taken in the hunt.

Beliefs and Traditions

The Tonkawa viewed the natural world as spiritually alive. Animals were considered messengers and helpers, especially the wolf, which played a major role in Tonkawa mythology. According to their creation stories, the Tonkawa were descended from a mythical wolf figure, and thus the wolf became their spiritual protector.

Spanish and Anglo accounts mention the Tonkawa practicing ritual cannibalism in warfare contexts, eating small portions of enemy flesh to absorb their spiritual power. Modern historians interpret these claims with caution, noting they often came from rival tribes or biased colonial accounts intended to justify military action against the Tonkawa. Regardless of accuracy, these stories contributed heavily to how settlers perceived the tribe.

Alliances and Conflicts

For much of their history, the Tonkawa were caught between warring nations. They clashed with the Apache in earlier centuries and were later forced into conflict with the Comanche, who moved into Texas around the 1700s and dominated the buffalo ranges the Tonkawa relied on.

Surrounded by hostile powers, the Tonkawa aligned themselves with:

- Spanish authorities during the mission period

- Texan settlers during the frontier era

- The Republic of Texas and later the U.S. Army

Because of their deep knowledge of Texas terrain, the Tonkawa became highly valued as scouts and trackers, often working alongside the Texas Rangers and U.S. cavalry units.

Missions and Early European Contact

Spanish missionaries attempted to settle the Tonkawa in missions such as:

- Mission San Xavier del Bac on the San Gabriel River

- San Antonio de Valero (the Alamo)

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria

The goals were to convert them to Christianity and encourage agriculture. While some Tonkawa participated in mission life, many rejected full settlement, preferring to maintain mobility. The missions, however, became important hubs for trade, diplomacy, and food during difficult seasons.

Texas Statehood and Military Service

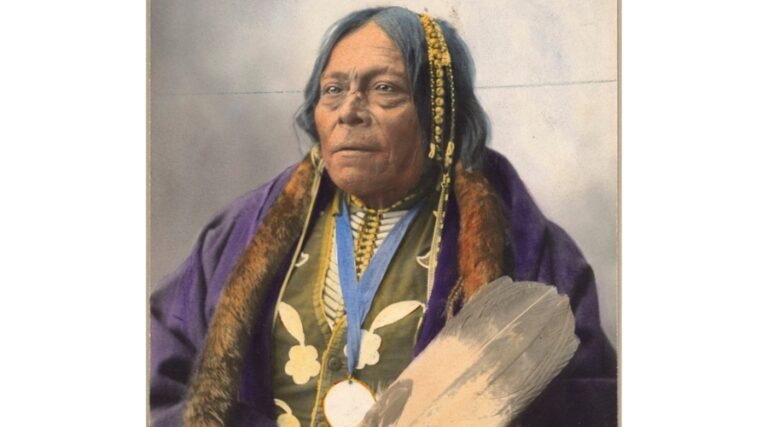

During the Republic of Texas era, the Tonkawa were known as fierce allies of Texan settlers. Chief Placido, one of the most famous Tonkawa leaders, developed a strong friendship with Edward Burleson and Sam Houston. He and his warriors fought alongside Texans in campaigns against the Comanche and in the Mexican-American War.

By the 1850s, the Tonkawa were confined to the Brazos Indian Reservation alongside other tribes. Even then, they continued to serve as scouts for the military, providing vital intelligence and protecting wagon routes.

Removal and Hardship

Despite their loyalty, the Tonkawa were not spared from federal removal policies. In 1859, they were forcibly relocated from Texas to Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma). During the Civil War, while staying near Fort Cobb, they were attacked by a coalition of rival tribes in what became known as the Tonkawa Massacre of 1862. Nearly half the tribe was killed.

Survivors were moved multiple times before eventually settling in present-day Kay County, Oklahoma, where their descendants live today.

The Tonkawa Today

The Tonkawa Tribe of Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe with its headquarters in the city of Tonkawa. Today, the tribe manages cultural preservation programs, economic enterprises, and language revitalization initiatives. Annual gatherings celebrate Tonkawa heritage through dance, storytelling, and traditional foods.

Legacy in Texas

Though the Tonkawa no longer live in Texas as a distinct community, their impact remains visible in:

- Place names and historical markers

- Archaeological sites in Central Texas

- Museum exhibits and preservation sites

- Military history records celebrating Tonkawa scouts

Their story is inseparable from the history of Texas—shaping the state’s frontier culture, influencing settler survival, and reminding us of the resilience of Indigenous peoples.