Long before European explorers set foot on the Gulf Coast, the Karankawa people lived among the windswept shores, tidal marshes, and barrier islands of Texas. Known for their tall stature, impressive physical strength, and mastery of life in the coastal environment, the Karankawa have long captured public imagination. Although often misunderstood, they played an essential role in shaping the early history of Texas.

This article explores who the Karankawa were, how they lived, and what ultimately happened to them, using the same engaging format as the Texas Happens pieces on the Comanche and Caddo tribes.

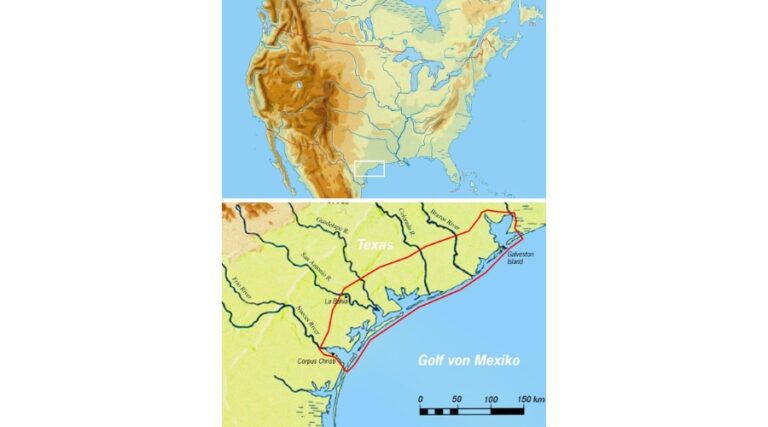

Homeland on the Texas Gulf Coast

The Karankawa inhabited the Texas Gulf Coast from Galveston Bay down to Corpus Christi Bay, including barrier islands and the inland prairies near the coast. This region’s bays, lagoons, and estuaries offered rich fishing grounds, while the inland areas provided game and plant foods. Their territory also made them one of the first Indigenous groups encountered by Europeans shipwrecked on Texas shores.

Seasonal Lifestyle and Shelter

Unlike agricultural tribes, the Karankawa were semi-nomadic, moving seasonally to follow food sources. In winter, they lived near the coast, where seafood was most plentiful. In warmer seasons, they traveled inland to hunt deer, bison, and gather plant foods.

Housing consisted of wigwams made of willow branches covered with animal hides or woven mats, which could be easily assembled and moved. These circular huts were sturdy enough to withstand coastal storms and provided insulation against wind and heat.

Food, Tools, and Daily Life

The Karankawa diet was well adapted to their environment. They ate:

- Fish, oysters, clams, and sea turtles from the bays

- Deer, bison, and small game during inland migrations

- Prickly pear fruit, mesquite beans, and roots

They used dugout canoes to travel along the coast and were skilled at navigating shallow waters. Tools were made from stone, bone, and shells. They also crafted baskets and pottery for daily use and trade.

Appearance and Distinctive Customs

Historical observers noted that the Karankawa were tall and powerfully built, often over six feet in height. They coated their skin with alligator or shark grease to protect against mosquitoes and sun exposure—an adaptation essential to life near the coast.

They also practiced body piercing and tattooing, and some bands were reported to use forehead shaping in infancy, a cultural custom found among several Native nations.

Language and Social Organization

The Karankawa spoke a unique language known as Karankawan, which does not appear to be closely related to any other known Native American language. They organized themselves into small bands of 30 to 40 people, each led by a chief. These bands shared cultural practices and would unite for trade, ceremonies, and defense.

Their spiritual beliefs centered on the natural world. Ceremonial gatherings often included singing, dancing, and ritual feasting that strengthened community ties.

First Contact with Europeans

The Karankawa were among the first Indigenous peoples in Texas to encounter Europeans. In 1528, explorer Cabeza de Vaca was shipwrecked near present-day Galveston Island and lived among Karankawa-speaking people for several years. His accounts provide some of the earliest descriptions of Native life in Texas.

Later, in the late 1600s, French explorer La Salle encountered the Karankawa while attempting to establish a settlement near Matagorda Bay. These early encounters were often marked by misunderstanding and conflict, setting the stage for future tensions.

Relations with the Spanish and Other Tribes

Throughout the 18th century, Spanish missionaries attempted to settle the Karankawa into missions, particularly around Goliad and Refugio. However, most Karankawa bands resisted mission life, preferring their traditional seasonal movements.

They also experienced conflict with other tribes such as the Apache and Tonkawa, as well as European settlers who built homes and ranches on Karankawa territory.

Misconceptions and Myths

The Karankawa were often portrayed in European and American accounts as “fierce” or “hostile,” and some writings accused them of ritual cannibalism. While some scholars believe there may have been ritual practices involving enemies killed in combat, these accounts were often exaggerated or biased, used to justify military campaigns against them.

Modern historians emphasize that the Karankawa were no more violent than other tribes defending their homelands.

Decline and Displacement

By the early 1800s, increased settlement along the Texas coast brought disease, displacement, and conflict. As settlers moved into the region, the Karankawa were pushed further south and west. Many died from smallpox and measles, while others were killed in conflicts with Mexican and Texian forces.

By the mid-1800s, the Karankawa as a distinct tribe were no longer recorded in official accounts. Some survivors are believed to have moved into Mexico or assimilated into other Indigenous communities.

Legacy and Cultural Memory

Although the Karankawa are often referred to as “extinct,” descendant communities and cultural advocates still exist today and work to preserve their history. The story of the Karankawa is a reminder of the deep Indigenous roots of Texas and the importance of coastal life in Native history.

Their legacy endures in place names, archaeological sites, and renewed interest by historians and descendants who are reclaiming and reviving ancestral knowledge.

Conclusion

The Karankawa were expert navigators of land and sea, whose lives were intimately connected to the Gulf Coast. Though often misunderstood, they were one of the most important Indigenous peoples in early Texas history. Their courage, skill, and resilience shaped the identity of the Texas coast long before European settlement—and their legacy continues to be rediscovered today.