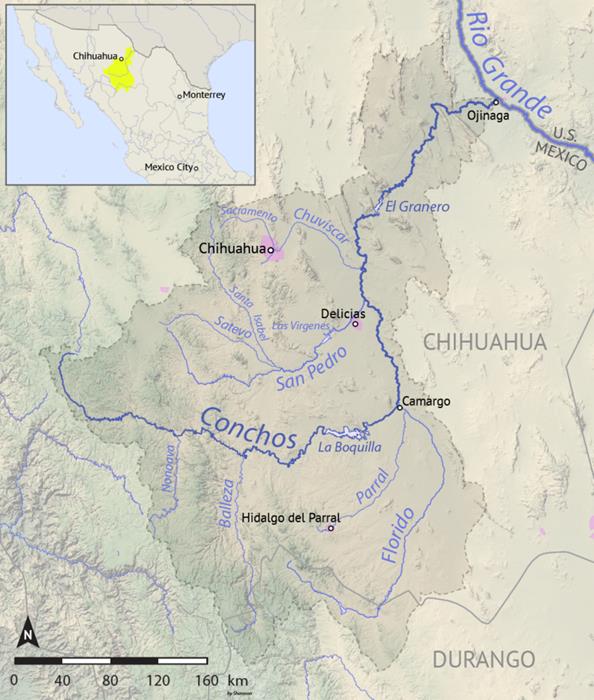

Long before Texas became a state, the fertile valleys of far West Texas were home to the Concho people, a group of river-dwelling communities who thrived along the Río Conchos and Río Grande. Sometimes called the Conchos Tribe, they were among the La Junta Indians, a name the Spanish used for several Native groups who lived near La Junta de los Ríos, where the two great rivers meet near today’s Presidio, Texas, and Ojinaga, Mexico.

Their story is one of adaptability, survival, and resilience in the challenging desert borderlands.

The Land of La Junta de los Ríos

The Conchos lived in a unique natural crossroads where two rivers nourished the desert. The confluence provided fertile soil, abundant fish, and access to water in a harsh environment. This region—La Junta de los Ríos—became an oasis of culture, trade, and agriculture, supporting several semi-sedentary groups.

Archaeologists have discovered that the Conchos and their neighbors built mud-plastered jacales, farmed the floodplains, and used stone tools and pottery influenced by both Casas Grandes (in Chihuahua) and Jornada Mogollon cultures to the north.

Origins and Daily Life

The Conchos were closely related to other Uto-Aztecan and Puebloan-influenced tribes, forming part of a diverse network of river communities. They cultivated maize, beans, and squash, while also gathering mesquite beans, agave, cactus fruit, and nuts.

Fishing was central to their diet—so much so that the name “Concho,” given by the Spanish, likely comes from the Spanish word for “shell,” referencing their riverine lifestyle and shell jewelry.

They built small villages along the Río Conchos and lower Río Grande, where extended families shared communal homes and storage pits. Their days revolved around irrigation farming, food gathering, and ritual gatherings tied to the rhythm of the seasons.

Neighbors and Trade Networks

The Conchos were not isolated. Their villages connected through trade and kinship with groups like the Jumano, Julimes, Patarabueyes, Suma, and Manso peoples. The region’s location between northern Mexico and the Great Plains made it a hub for exchanging goods such as corn, hides, shells, salt, turquoise, and pottery.

These networks helped the Conchos endure environmental challenges and link distant cultures long before European contact.

First Encounters with the Spanish

The Conchos were among the earliest Texas-area peoples to meet Europeans. In 1535, Cabeza de Vaca passed near their homeland during his legendary trek across the Southwest. Later, in the 1580s, Spanish explorers Chamuscado-Rodríguez and Antonio de Espejo recorded visits to the thriving La Junta villages.

They described people living in organized settlements with granaries, cultivating crops, and maintaining active trade routes. For Spanish chroniclers, these peaceful, agricultural river dwellers stood in contrast to nomadic groups farther north.

Missions and Colonial Pressure

By the 17th century, Spanish missionaries began establishing outposts among the La Junta peoples, aiming to Christianize and settle them permanently. Missions such as San Cristóbal, San Francisco, and San Pedro appeared near the rivers, attempting to unite various local groups—including the Conchos—under Spanish rule.

However, mission life disrupted traditional structures. Epidemics, forced relocations, and raids by Apache and later Comanche bands eroded their population and stability. Over time, many Conchos either fled deeper into Chihuahua or merged with neighboring groups to survive.

Cultural Life and Social Structure

View this post on Instagram

Spanish records hint at a complex social and ceremonial life among the Conchos. Villages were led by chiefs who managed irrigation, planting, and community defense. Religious leaders guided rituals tied to planting and harvest seasons, and dances were held to mark celestial cycles and social events.

Their homes—built from wood, reeds, and mud plaster—were practical for the desert climate, while their crafts included woven mats, baskets, and shell ornaments. Though much of their language and spiritual life was lost over time, the archaeological record preserves traces of a once-flourishing society.

Decline and Dispersal

By the late 1700s, centuries of upheaval—disease, colonization, warfare, and assimilation—had taken a heavy toll. Many surviving Conchos were absorbed into Spanish-Mexican settlements or joined other tribes under new identities. The name “Concho” faded from official records, surviving mainly in geographic memory—through the Río Conchos, the Concho River in Texas, and Concho County.

Yet, traces of their culture endure in the people and traditions of northern Chihuahua and West Texas, where descendants still celebrate their river heritage and ancestral resilience.

Legacy in Texas Today

Though the Conchos as a distinct tribe no longer exist, their legacy endures through place names, archaeological sites, and oral traditions. The La Junta area near Presidio remains one of the most significant archaeological zones in Texas, with thousands of years of habitation revealing the importance of this river junction.

Today, historians and tribal descendants in both Texas and Chihuahua work to preserve the story of the Conchos, ensuring that their role in shaping the cultural landscape of the borderlands is never forgotten.

Conclusion

The story of the Concho people is a reminder that Texas history began long before written records—with communities who turned desert into farmland, rivers into lifelines, and diversity into strength. Their ingenuity and endurance still echo through the canyons and floodplains of West Texas, where two rivers meet and memory flows on.