Many many wonder – Does Texas have natural disasters? From hurricanes and floods to wildfires and tornadoes, Texas has seen it all when it comes to catastrophic events. The state’s diverse geography and climate play a huge role in this variety of disasters. Texas stretches from the humid Gulf Coast to the dry plains in the west, making it a prime spot for all sorts of extreme weather.

Coastal areas are often in the path of powerful hurricanes, while central and western regions face tornadoes and wildfires. And let’s not forget the industrial centers like Houston, which have their own unique risks.

Let’s take a look at some of the worst man made and natural disasters in Texas history:

Yellow Fever Epidemic (1867)

Thousands of lives were lost during the 1867 yellow fever epidemic, which was one of the most devastating events in the history of the Lone Star State. No definite list of casualties was compiled, but entire towns were wiped out due to the disease. This epidemic is believed to be second to the 1900 Galveston hurricane in number of deaths.

The outbreak originated in Indianola in June, and the virus spread by way of infected persons to Galveston and then across East-Central Texas. The spread of the virus didn’t stop until November, during the first frost of the year. By then, 4,000 Texans has already died, including 393 US soldiers across the state.

Great Galveston Hurricane (1900)

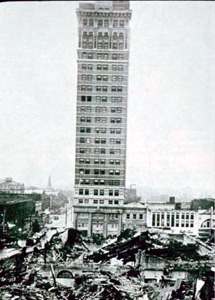

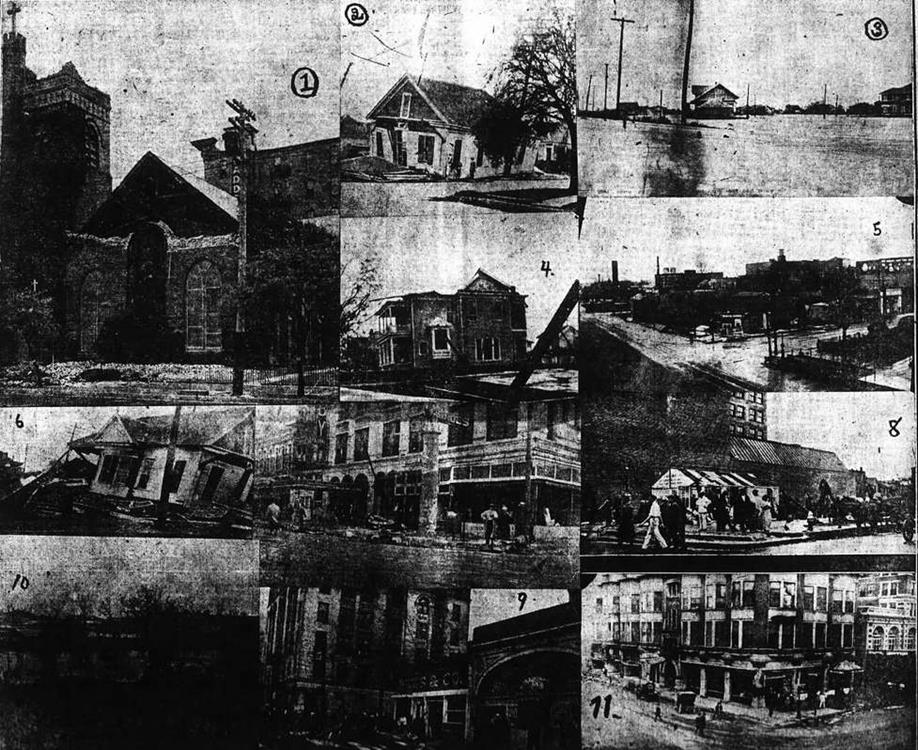

The infamous great hurricane that struck Galveston shores on September 8, 1900 remains the worst and deadliest hurricane in Texas and in the history of the United States. This category four hurricane left around 6,000 to 12,000 people dead (the number most cited in official reports is 8,000). To put this death toll to perspective, this Great Galveston Hurricane killed more people than the total of all those who died in every tropical cyclone to make landfall in the United States since.

The hurricane sustained winds of 145 mph and caused $700 million (in 2017 USD) in damages, making it the second costliest hurricane in the US ever. Weather forecasters issued a warning for residents and tourists to move to a higher ground, but the warnings were ignored. A 15-foot surge flooded the city and destroyed many homes and buildings in the process. The most advanced city in Texas was nearly destroyed by one of the largest natural disasters in Texas.

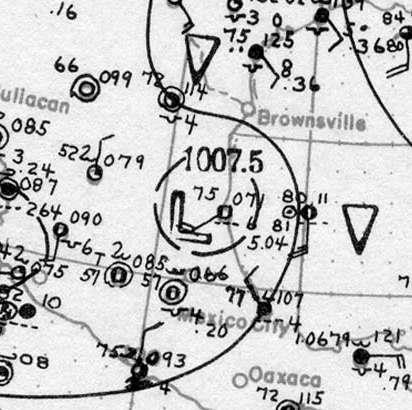

Galveston Hurricane (1915)

Fifteen years after a monstrous hurricane that wrecked Galveston, another devastating hurricane decided to strike the city. In August 1915, Galveston is hit again by a tropical cyclone that caused extensive damages in the port city. It made landfall in the area as a Category Storm, leaving five to six feet of water in many businesses. The devastation would have been even worse than the 1900 hurricane, but the newly completed Galveston Seawall mitigated the disaster.

Still, the storm caused $109.8 billion (in 2018 USD) in the United States and killed more than 400 people. It was the fourth most catastrophic hurricane in US history in terms of damage costs.

Corpus Christi Hurricane (1919)

On September 14, 1919, a powerful Category 4 hurricane roared ashore near Corpus Christi with an estimated 16-foot storm surge, wrecking ships in the bay and sweeping low-lying neighborhoods off the map. The official Texas death toll is typically cited around 284–287, but historians and state agencies note a realistic estimate of 600–1,000 deaths once offshore and unrecorded casualties are included—placing it among the deadliest U.S. Gulf Coast storms of the century.

The devastation spurred long-term coastal protections and civic rebuilding. Within years, Corpus Christi opened its deep-water port (1926) and later expanded seawall and harbor defenses, reshaping the city’s growth through the 20th century.

Central Texas Flood (1921)

In September of 1921, rain fell throughout Central Texas and was received as a relief because it broke more than two-month-long droughts. However, within a 24-hour period, some parts of Texas experienced a record-breaking 38 inches of rainfall. It also caused floods in much of Austin and San Antonio, resulting in the deaths of 224 individuals. Houses and entire families were washed away, and damage to local infrastructure was extensive and irreparable. Fourteen of the 27 bridges over the San Antonio River were destroyed, and many buildings in the heart of the city had to be demolished.

The hardest hit area was Williamson County, north of Austin, where twice as many lives were lost as in San Antonio. According to records, it was the worst flood in Texas history. The flood waters measured around 8,000 acre-feet. This disaster caused a 10-year overhaul of flood control measures and river improvements in San Antonio to help better thwart future natural disasters in Texas.

Texas City Disaster (1947)

The Texas City Disaster in 1947 was an industrial accident that occurred on the Port of Texas City at Galveston Bay. On April 16, 1947, SS Grandcamp exploded while it’s moored in Texas City, and the cargo included ammonium nitrate, fertilizers and a highly explosive substance. The explosion set off a chain of fires, completely destroying the entire ship, dock area, and a thousand nearby homes and buildings. It also caused a 15-foot tidal wave. This incident killed 26 firemen and destroyed all their firefighting equipment. Around 400 to 600 people were killed, with as many as 4,000 people injured.

Unfortunately, another ship nearby was also carrying ammonium nitrate – SS High Flyer. The ship caught fire during the first explosion, but it was towed away from the mainland before it exploded after 16 hours.

Texas Drought of Record (1950–1957)

Texas’ longest and most consequential drought in recorded history stretched through much of the 1950s. By late 1956, 244 of 254 counties were designated disaster areas as reservoirs shrank, crops failed, and ranchers liquidated herds; the drought finally broke with widespread flooding in 1957. The event became the benchmark—Texas’ “drought of record”—for water-supply planning.

This crisis reshaped state policy. Lawmakers and local leaders embarked on a reservoir-building surge and long-range water planning that still guides Texas today; later technical studies continue to use the 1950s as the baseline for stress-testing water systems.

Waco Tornado (1953)

Texas has seen its share of great tornadoes, but none as deadly as the Waco Tornado that struck Waco on Mother’s Day of 1953. The twister touched down in the town of Lorena and moved northeast toward Waco. As it moved, it grew to nearly a third of a mile wide and was classified as an F5 tornado. This violent tornado killed 114 people, injured 597, and left a 23-mile swatch of destruction that destroyed 600 homes and damaged 1000. Search and rescue has become difficult as some people had to wait up to 14 hours to be rescued.

The impact of the tornado prompted the Texas Tornado Warning Conference in June of the same year, where officials discussed and improved tornado warning systems to prevent future death tolls like that of what the Waco tornado left. This twister was one of the deadly series of at least 33 tornadoes that hit at least ten different states in the US on May 9-11, 1953, and this one was the deadliest.

Hurricane Carla (1961)

Among the most intense Texas landfalls of the 20th century, Hurricane Carla struck near Port O’Connor/Matagorda Island in September 1961 with Category 4 force. Carla’s enormous size drove a record Texas storm surge of ~22 feet in Port Lavaca, pushed water miles inland, and spawned dozens of tornadoes across Texas and Louisiana. Despite the scale, the death toll—often cited around 43—was limited compared with potential, in part because roughly 500,000 Texans evacuated, then the largest peacetime evacuation in U.S. history.

Carla’s widespread wind and surge damage from Brownsville to Port Arthur and well inland became a case study for forecast communication and emergency management, and it remained a benchmark Gulf hurricane for decades.

Wichita Falls “Terrible Tuesday” Tornado (1979)

On April 10, 1979, an immense F4 wedge tornado—part of the Red River Valley outbreak—cut a mile-wide path across Wichita Falls at the evening commute. The storm killed 45–46 people, injured ~1,500–3,200, destroyed or damaged thousands of homes, and made national history as the costliest U.S. tornado to that time (hundreds of millions in losses). A famous FEMA film, Terrible Tuesday, later documented the event and its aftermath.

The disaster transformed local building standards and emergency operations. It also influenced national preparedness messaging—reinforcing the dangers of vehicle evacuation during urban tornadoes and the importance of interior sheltering and timely warnings.

Delta Airlines Flight 191 Crash (1985)

On August 2, 1985, Delta Airlines Flight 191 crashed on approach at the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. It was a rainy Friday, and the jumbo jet encountered a microburst – a downdraft that’s very hazardous for aircraft – sending the plane careening along the ground north of runway 17L. The plane struck a car on Texas Highway 114, killing its driver, then exploded into a fireball as it slammed into large water tanks.

This unfortunate plane crash killed 136 passengers and crew on board, plus the driver of the car on the highway. Twenty-seven people survived this crash. According to the investigation, although the pilot was competent and experienced, he lacked training in how to deal with microbursts. After the crash, pilots were required to train more extensively in handling and reacting to microbursts and how to take quick, evasive actions.

New London School Explosion (1987)

In March of 1987, an unfortunate school accident led to the death of more than 295 students and teachers and resulted in a building collapse. A natural gas leak caused a deadly explosion in the basement of New London School in Rusk County.

The accident happened because a manual training instructor turned on a sanding machine in an area filled with natural gas. It caused an ignition in the air and the flame moved under the building before exploding. This caused the building to collapse from the ground up.

Tropical Storm Allison (2001)

Allison stalled and looped over Southeast Texas in June 2001, unleashing 20–40+ inches of rain in parts of the Houston area. It became, at the time, the costliest U.S. tropical storm, with damage exceeding $5–6 billion. Twenty-two deaths occurred in Texas, and critical facilities—including the Texas Medical Center—were inundated as bayous overtopped and freeways became rivers.

The catastrophe spurred the Tropical Storm Allison Recovery Project (TSARP), a major FEMA–Harris County initiative that remapped flood risk across 22 watersheds and modernized local floodplain data. TSARP’s high-resolution models and outreach reshaped permitting and mitigation in the nation’s third-largest county and set a template for later flood-risk communication.

Hurricane Rita Evacuation Disaster (2005)

With memories of Katrina fresh, more than 2.5 million Texans evacuated ahead of Hurricane Rita—one of the largest mass movements in U.S. history. Gridlocked highways, triple-digit heat, fuel shortages, and breakdowns turned the exodus itself into a calamity. Academic and public-health tallies place evacuation-related deaths at roughly 100 or more statewide, far exceeding direct storm fatalities in Texas. Among the worst incidents was a nursing-home motorcoach fire on I-45 near Wilmer that killed 23 evacuees.

Post-Rita reforms focused on contraflow planning, fuel staging, medical/assisted-care evacuation, and heat safety protocols for multi-hour traffic jams—changes that informed later hurricane playbooks along the Gulf Coast.

Hurricane Ike (2008)

Hurricane Ike, a Category 4 hurricane, struck the Texas Gulf Coast on September 13, 2008. It caused widespread destruction, particularly in Galveston and the Houston metropolitan area. Ike’s powerful winds and storm surge led to significant flooding, extensive property damage, and power outages affecting millions of residents.

The hurricane resulted in 195 deaths and approximately $30 billion in damages. Ike’s impact was so severe that it led to numerous changes in building codes and disaster preparedness plans across Texas. This quickly became one of the worst natural disasters in history.

Bastrop County Complex Fire (2011)

The Bastrop County Complex Fire, the most destructive wildfire in Texas history, ignited on September 4, 2011. Over 34,000 acres were burned, and nearly 1,700 homes were destroyed. The fire, driven by high winds and drought conditions, caused two fatalities and significant environmental damage, including the loss of the endangered Houston toad’s habitat.

The fire’s aftermath prompted significant changes in wildfire management and community preparedness efforts, highlighting the importance of fire-resistant building practices and emergency evacuation plans.

Hurricane Harvey (2017)

Hurricane Harvey, a Category 4 storm, made landfall on the Texas coast on August 25, 2017. It is one of the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history, causing unprecedented flooding in the Houston area and other parts of southeastern Texas. Harvey dumped more than 60 inches of rain in some areas, leading to widespread catastrophic flooding, displacing over 30,000 people, and causing 107 confirmed deaths. The economic impact exceeded $125 billion.

The response to Harvey highlighted the need for improved flood infrastructure, better urban planning, and more robust emergency response strategies.

Winter Storm Uri & the Texas Power Crisis (2021)

In mid-February 2021, a historic Arctic outbreak gripped Texas for days, crippling the state’s isolated power grid and triggering rolling blackouts that became multi-day outages for millions.

At the peak, roughly 4.5 million Texas customers lost electricity; water systems failed as treatment plants and pumps went dark or froze, and more than 14 million people were placed under boil-water notices. The Texas Department of State Health Services ultimately attributed at least 246 deaths to the storm, a toll that drew national and international scrutiny.

Beyond the human cost, Uri produced staggering economic losses—commonly cited estimates put total damage near or above $195 billion—while exposing cascading risks between electricity, gas supply, and critical services. The crisis spurred statewide reforms, including mandatory weatherization and new reliability rules for generators and fuel suppliers, even as analysts warned vulnerabilities remained.

Smokehouse Creek Fire, Texas Panhandle (2024)

The Smokehouse Creek Fire exploded across the Panhandle in late February 2024, ultimately burning about 1.06 million acres—by far the largest wildfire in Texas history.

At least two people were killed, thousands of head of cattle were lost, and hundreds of homes, barns, and miles of fencing and power infrastructure were destroyed, with smoke and ash plumes visible from space. The blaze was fully contained by March 16 after an all-hands response from local departments, the Texas A&M Forest Service, and partner agencies.

Investigators and lawmakers later tied ignition to utility equipment, with a Texas House committee concluding a decayed pole failed and Xcel Energy acknowledging its facilities were “involved” in the start. The finding fueled lawsuits and statewide calls for tougher vegetation management, equipment inspections, and dedicated aerial firefighting resources for rural regions prone to fast-moving grassfires.

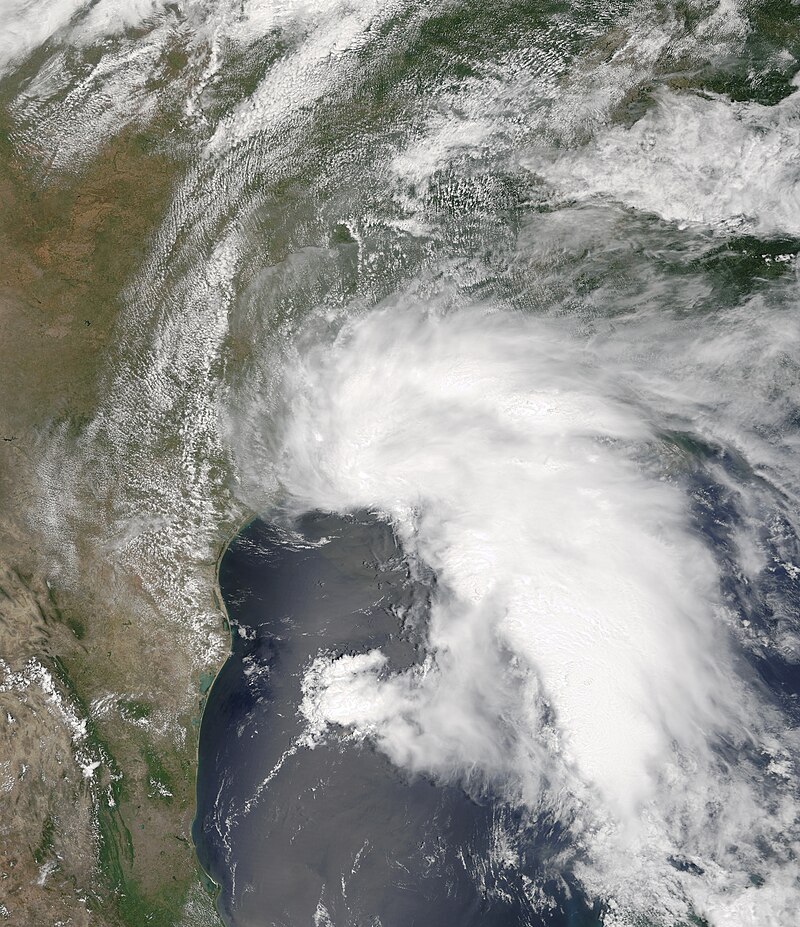

Hurricane Beryl (2024)

Beryl made landfall near Matagorda on July 8, 2024, with damaging winds and drenching rain that toppled trees and transmission structures across Greater Houston and East Texas. More than 2.6 million customers lost power—many for days during dangerous heat—drawing international attention to prolonged outages and the strain on medically vulnerable residents.

As recovery unfolded, the Texas death toll climbed as heat-related fatalities were confirmed among households left without air conditioning; later counts placed statewide deaths at least in the mid-30s. Officials and regulators opened inquiries into grid and utility performance, while local leaders pressed for hardened lines, improved outage communication, and faster mutual-aid mobilization for urban wind events.

Central Texas / Hill Country Floods (2025)

Over the July 4 weekend, a predawn flash flood exploded along the Guadalupe River and its tributaries, turning camps and riverfront resorts in Kerr County into disaster zones within hours. Gauges showed a historic, near-vertical rise—camp leaders reported the river jumped 30+ feet in about 3½ hours—with the Guadalupe at Kerrville cresting at 34.29 feet, the city’s third-highest flood on record (trailing 1932 and 1987); upstream near Hunt, the event set an all-time record.

Entire neighborhoods, low-water crossings, and RV sites were swept away before sunrise. The human toll was staggering: authorities ultimately identified 119 victims in Kerr County, part of at least 135 statewide deaths.

Two of the worst-hit sites became national symbols of the tragedy—Camp Mystic, where 27 campers and staff died, and the HTR TX Hill Country resort near Ingram/Kerrville, where at least 37 people were lost as trailers and “tiny homes” were carried off the riverbank.

Conclusion

Understanding the worst disasters in Texas history helps us appreciate the resilience and strength of its communities. Each event has taught valuable lessons in preparedness and response from hurricanes and floods to wildfires and tornadoes. By learning from the past, we can better protect and support our communities in the face of future challenges.