The Fredonian Rebellion (1826–1827) was Texas’s first independence attempt, sparked when empresario Haden Edwards threatened to invalidate existing settlers’ land claims in East Texas.

After a disputed election in Nacogdoches, Edwards and supporters declared the “Republic of Fredonia,” forming an unstable alliance with Cherokee leaders. The rebellion quickly collapsed when Mexican forces arrived, forcing the Edwards brothers to flee.

Though brief, this forgotten uprising laid groundwork for the successful Texas Revolution a decade later.

The Empresario System and Haden Edwards’ Land Grant

While Mexico sought to populate its northern frontier after independence, the empresario system emerged as its primary colonization strategy. In 1825, the Mexican government granted Haden Edwards a contract to settle 800 families in eastern Texas, making him one of the few early empresarios in the region.

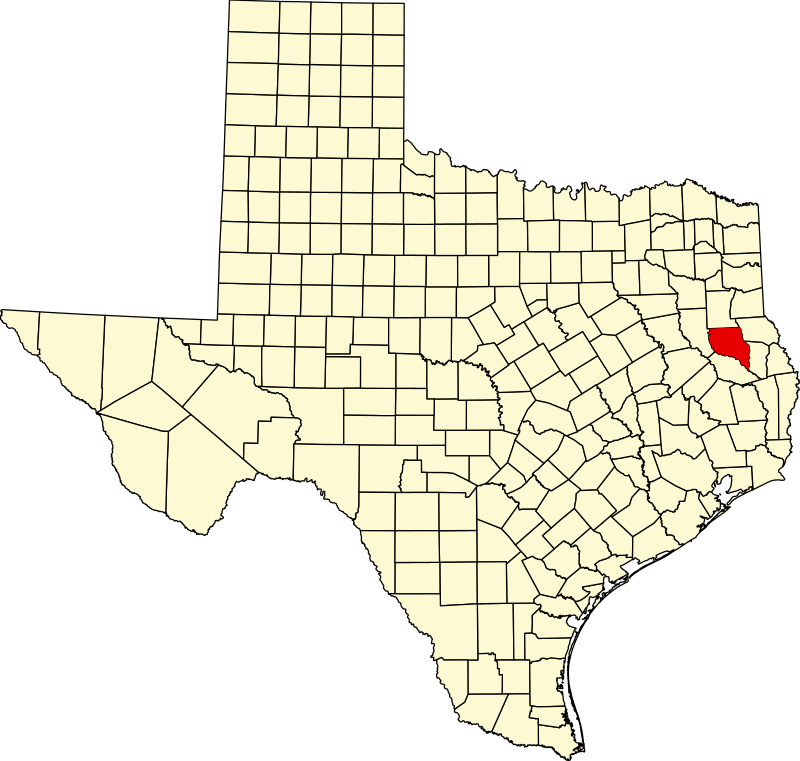

Edwards’ grant around Nacogdoches was situated in contested territory, bordering the Neutral Ground, Native American lands, and Stephen F. Austin’s colony. This challenging location, combined with the scarcity of prior land grants (only 32 recorded), set the stage for conflict. Edwards’ aggressive approach toward Spanish-speaking residents who’d settled before his arrival created immediate tensions. These hostilities reached a breaking point during the 1826 alcalde election, which pitted longtime inhabitants against Edwards’ new settlers.

Similar to Edwards’ situation, Austin’s land grant in 1823 allowed him to settle families in the Bastrop region, though with considerably less conflict than Edwards experienced.

Tensions Between Old Settlers and New Immigrants

The cultural powder keg that exploded in eastern Texas during 1825-1826 had been building long before Haden Edwards posted his notorious proclamation. In a region with barely three dozen prior land transactions, Edwards’ grant area was already a complex tapestry of established Spanish families and indigenous claims.

When Edwards threatened to invalidate existing land titles unless residents could prove ownership, you’d have witnessed immediate division in Nacogdoches. The political landscape deteriorated further during the 1826 alcalde election, which pitted Edwards’ brother-in-law against Samuel Norris, who’d support from old settlers.

After Edwards’ candidate initially won, Mexican authorities and political chief José Antonio Saucedo reversed the results, choosing Norris instead. This decision inflamed Edwards’ colonists, who saw it as proof the Mexican government favored established residents over American newcomers.

The area’s Caddo tribal lands were caught in this territorial dispute, further complicating matters as their ancient trade networks and settlements predated both Spanish and American claims by centuries.

The Disputed Election and Mexican Authority

At the heart of the brewing conflict stood a seemingly simple municipal election that would ultimately ignite the first armed rebellion against Mexican authority in Texas. In 1826, Nacogdoches became the flashpoint when American immigrants, encouraged by empresario Haden Edwards, clashed with established Spanish-speaking residents over local governance.

When Mexican authorities intervened in the disputed election, they reversed the results and installed Samuel Norris as alcalde. This decision infuriated the newcomers from the United States. Norris then declared that Edwards had improperly allocated land and ordered the eviction of several immigrant settlers.

The tension boiled over when Edwards’ supporters arrested Norris and other Mexican officials in late 1826. Mexico responded by dispatching troops to reassert control, setting the stage for what would become the Fredonian Rebellion. This early conflict foreshadowed the later strategic importance of locations like Presidio La Bahía during the Texas Revolution.

Declaration of the Republic of Fredonia

As tensions reached a breaking point in Nacogdoches, Edwards and his supporters took a bold step that would echo through Texas history. On December 21, 1826, they signed the Fredonian Declaration of Independence, establishing an autonomous republic separate from Mexico.

Haden Edwards appointed his brother Benjamin to lead their military forces while securing an alliance with Cherokee leaders Richard Fields and John Dunn Hunter. Their partnership was symbolized in the republic’s red and white striped flag. The rebels desperately appealed to the United States for recognition, hoping for support against Mexican authority.

The Fredonian Rebellion was quickly condemned by settlers loyal to Mexico. Peter Ellis Bean, working on behalf of officials in San Antonio, helped organize forces that would ultimately crush this first Texas independence movement before it could gain momentum.

Failed Alliances and Military Response

From the beginning, Edwards’ fledgling republic faced a critical challenge that would ultimately seal its fate – unstable alliances. You’ll note that while the Fredonian Rebellion initially sought Cherokee support, Mexican authorities swiftly undermined this essential partnership, convincing the tribe to withdraw.

The response was decisive. Mexican forces under Lt. Col. Ahumada marched from San Antonio to Nacogdoches, efficiently crushing the rebellion. Surprisingly, Stephen F. Austin and other Texian militia joined these Mexican troops, revealing deep divisions among settlers who weren’t ready to back independent republics.

Faced with this overwhelming opposition, the Fredonians retreated across the Sabine River into U.S. territory. This military response demonstrated Mexico’s determination to maintain control over Texas and suppress secessionist movements, effectively ending this first attempt at Texas independence.

Collapse of the Rebellion and Edwards’ Flight

The Fredonian Rebellion crumbled with surprising speed once Mexican and Austinian forces reached Nacogdoches on January 31, 1827.

You’d find it notable that the Edwards brothers abandoned their position at the Old Stone Fort and fled across the Sabine River, leaving their short-lived republic behind. Their Indian allies quickly withdrew support, sealing the rebellion’s fate in Mexican Texas.

The consequences of this failed uprising were significant:

- Edwards’ empresarial grant was immediately declared forfeit

- The deaths of Indian leaders Hunter and Fields resulted directly from their association with the rebellion

- A deep polarization emerged between old settlers and newcomers in Austin’s colony

This swift collapse demonstrated Mexico’s resolve to maintain control while exposing the fragility of revolutionary ambitions without broader support.

Legacy and Influence on the Texas Revolution

While the Fredonian Rebellion itself collapsed rapidly, its aftershocks reverberated throughout Mexican Texas for years to come. You can trace a direct line from this failed uprising to the successful Texas Revolution that followed. When the Mexican Indian agent arrived in Nacogdoches on January 31, 1827, to help quell the rebellion, he witnessed firsthand the simmering discontent that would soon boil over.

The rebellion highlighted the fundamental incompatibility between Spanish and Mexican governance and the ambitions of Texas settlers. Though crushed militarily, the Fredonian spirit lived on, teaching future revolutionaries valuable lessons about organization and the need for broader support. This forgotten chapter of Texas history served as an essential dress rehearsal, revealing both the challenges and possibilities of independence that would define the Texas Revolution.