Texas beer got its start in quiet corners. Folks brewed in kitchens, sheds, and backyards, using what they had and what they remembered. People brewed because it brought comfort. It kept them connected to their roots and gave them something steady in unfamiliar surroundings.

That kind of brewing didn’t fade with time. It adjusted, stuck around, and grew with the state. The story isn’t always smooth, but it’s worth following.

If you want to understand how beer became part of life in Texas, keep reading. The roots run deep.

Early Beer in Texas (1800s)

The story of Texas beer begins with settlers who came looking for a new life but held tight to old ways. Many of them were Germans who made their way to Central Texas in the mid-1800s. They planted roots in towns like New Braunfels, Fredericksburg, and Schulenburg. With them came well-worn brewing knowledge — no-frills, proven methods they had used for generations. Their equipment was basic, and their ingredients were often local or improvised. Still, the beer they made felt like home.

The First Texas Breweries

By the mid-1800s, brewing in Texas began moving out of homes and into organized operations. One of the first known commercial breweries was the Menger’sWestern Brewery, founded in 1855 by William A. Menger in San Antonio, just steps from the Alamo. It served local saloons and hotels and laid the groundwork for the city’s rich brewing tradition. Without refrigeration, early brewers stored their beer in natural limestone cellars or cooled it using ice harvested during the winter.

Making Beer in a Hot Climate

Brewing in Texas took patience, especially in the heat. The Hill Country offered a few advantages — natural springs, rock outcroppings, and thick-walled buildings that stayed cooler than the midday air. Brewers used wood-fired kettles to boil their grain, and fermentation took place in wide, open vessels. There were no temperature controls, so timing mattered. They reused yeast from batch to batch and brewed with what the land or local merchants could supply.

Community Over Commerce

Most of the beer never left town. Folks filled buckets and tin pails, took them home, and drank them before the beer could turn. These brews showed up at social gatherings, church events, and weekend dances. They became part of the rhythm of daily life. In many cases, beer served more as a shared staple than a luxury item.

Holding on to Tradition

Early Texas brewers weren’t chasing growth charts or expansion plans. They brewed to keep something familiar close by. In a state where work was hard and comfort was earned, beer offered a steady reminder of where folks had come from — and what they hoped to preserve.

Prohibition and Its Aftermath (1920–1933)

In 1920, the 18th Amendment took effect, and with it came a sudden stop to legal beer production across the country. In Texas, saloons shuttered, bottles disappeared from store shelves, and brewers faced a choice: pivot or vanish. The public face of beer may have faded, but the act of brewing didn’t vanish with it. People simply took it indoors and out of view.

The Impact on Texas Breweries

Before Prohibition, San Antonio stood out as a brewing hub. Its breweries, many of them family-owned, had started to find stability and growth. That momentum came to a halt once federal law made alcohol production illegal. Some breweries tried to stay afloat by shifting to other products.

Lone Star Brewery, once a thriving operation, closed down entirely. Others, like Spoetzl Brewery in Shiner, adapted in order to survive. Spoetzl stayed active by producing “near beer,” a low-alcohol substitute that stayed just within the limits of the law, and by selling ice to nearby customers.

Plenty of breweries had fewer options. Some dismantled their operations. Others let their equipment rust, holding out hope that the law would change. The ones who stayed in business did so by walking a narrow line — making just enough to get by without crossing too far into federal violation.

Home Brewing and Hidden Batches

Even though the law banned production and sale, it didn’t erase demand. People across Texas kept brewing, just not out in the open. Sheds, barns, kitchens, and basements turned into makeshift breweries. Supplies moved quietly, sometimes hidden under sacks of grain or barrels of oil. Recipes were passed along in whispers, scribbled on paper, or taught by memory.

In dry counties — many of which remained that way even after repeal — bootleggers operated with caution. Homemade batches were shared at gatherings, sold through side doors, or consumed in private. Beer didn’t disappear from the state. It simply took a different route to get to the glass.

Repeal and a Slow Return

The end of Prohibition in 1933 didn’t bring an instant comeback. Legal brewing returned, but the landscape had changed. Many old breweries couldn’t recover. Equipment had fallen into disrepair. New regulations made restarting difficult. Even after the federal ban was lifted, Texas counties still had the right to decide their own alcohol policies. Some remained dry for decades.

For the few breweries that managed to hold on — including Spoetzl — the end of Prohibition brought a slow but welcome chance to re-enter the market. They didn’t reopen to fanfare or fast profits. They reopened with grit and the hope that beer could once again find its place in public life.

The Industrial Era and the Rise of Shiner (1940s–1980s)

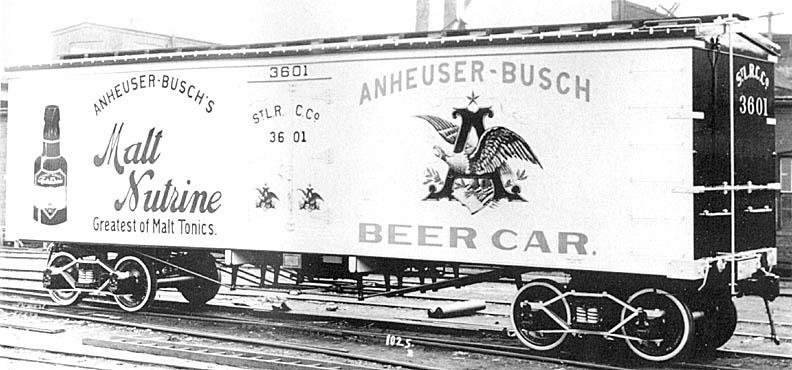

Once Prohibition ended, beer returned to the legal market, but the brewing industry no longer looked the same. Large national companies wasted no time in ramping up production. With deep pockets and broad distribution networks, breweries like Anheuser-Busch, Schlitz, and Pabst moved quickly into Texas. They brought uniform branding, modern bottling lines, and a level of consistency that appealed to store owners and bar managers across the state.

Their growth didn’t leave much room for smaller, local brewers. The beer aisle grew more crowded with national labels, while regional brews struggled to get shelf space or maintain volume. Advertising, which had once been a luxury, became a requirement. Billboards, radio spots, and later television ads pushed national brands into nearly every home.

A Shrinking Field

By the 1950s, the variety of local beer in many Texas towns had narrowed to a few familiar names — most of them brewed far outside the state. The subtle differences in style and recipe that had once reflected local tastes gave way to mass-produced lagers built for shelf life and nationwide appeal.

Breweries that had once served communities for decades either closed or folded into larger operations. In many areas, the idea of a “local beer” faded into memory.

Spoetzl Stays the Course

Amid the consolidation, Spoetzl Brewery in Shiner kept brewing. Founded in 1909 by German and Czech immigrants, it had already made it through Prohibition. After repeal, it found itself surrounded by bigger players with larger reach. But Spoetzl never chased expansion at the expense of its identity.

Rather than changing its product to match national trends, Spoetzl leaned into what it already knew. The brewery stuck with its established recipes and continued serving the community around it. Sales remained modest, but steady. While others scaled up or bowed out, Spoetzl focused on making beer that felt personal.

Shiner Finds Its Voice

In the 1970s, Spoetzl introduced Shiner Bock as a year-round offering. Originally brewed for Lent, this dark lager began drawing interest well beyond Lavaca County. At a time when most beers on the market leaned light and flavor-neutral, Shiner Bock stood out. It had body, malt character, and a tone that reminded some drinkers of what beer used to taste like.

Growth came gradually. The brewery didn’t rely on national campaigns or high-profile sponsorships. It found its customers one at a time — through bartenders, word of mouth, and folks who appreciated something a little different. People who tasted it remembered it, and many went looking for it again.

By the 1980s, Shiner Bock had earned more than a loyal following. It had become a symbol. In a state where most beer came from somewhere else, Shiner gave Texans something brewed with care, right in their backyard. It spoke quietly, but it stuck around.

The Craft Beer Renaissance in Texas (1990s–2010s)

Texas brewers in the 1990s faced tight laws. They couldn’t sell directly to customers. Distribution rules added extra costs. Still, a new generation of brewers got to work.

In 1994, Saint Arnold Brewing Company opened in Houston. It became the first legal craft brewery in Texas since Prohibition. Its founders brewed, sold, and fought to make it easier for others to do the same.

More Breweries Take Root

- In Austin, Live Oak Brewing Company stood out with German-style lagers and wheat beers.

- In Blanco, Real Ale Brewing Company focused on balance and water-driven flavor.

- In Fort Worth, Rahr & Sons brought brewing back to a city with a long-lost beer history.

They didn’t start with fancy buildings or deep pockets. They started with a need to make better beer.

Texas Beer Culture Grows

Taprooms brought people in. Brewery tours gave them something to talk about. Local beer became part of the experience, whether folks were visiting a small Hill Country town or kicking back in a city taproom.

By the time the 2000s ended, craft beer in Texas wasn’t struggling for attention. It had earned its place at the table.

New Wave of Iconic Texas Beers (2010s–Present)

With more freedom and support, brewers across Texas began to experiment. Some leaned into tradition. Others followed the flavor wherever it led. Taprooms gave them the room to try, fail, and try again.

Standouts by the Can, Bottle, and Tap

Electric Jellyfish – Pinthouse Brewing (Austin)

This hazy IPA helped introduce juicy, unfiltered hop-forward beers to a wider Texas audience. Brewed with a rotating cast of hops, it delivers layers of citrus, melon, and tropical fruit with a soft, pillowy mouthfeel. Electric Jellyfish became more than a flagship — it became a reference point for hazy IPAs in the state.

Atrial Rubicite – Jester King Brewery (Austin)

Brewed with fresh raspberries and aged in oak barrels, this wild ale helped put Jester King on the national map. Its bright acidity and earthy funk come from spontaneous fermentation and a hands-off brewing process that leans into nature. This beer didn’t just catch attention — it redefined what Texas beer could be.

Velvet Hammer – Peticolas Brewing Company (Dallas)

This imperial red ale drinks with purpose. It delivers a deep malt backbone with a sharp, clean bitterness that hangs around just long enough. Strong without being harsh, Velvet Hammer carved out a loyal following in Dallas and has held onto it with zero compromise in recipe or style.

Yellow Rose Smash IPA – Lone Pint Brewery (Magnolia)

Brewed using a single malt and a single hop — Mosaic — Yellow Rose stands out for its bold aroma and fruit-forward profile. It pours hazy gold and delivers flavors of pineapple, grapefruit, and a hint of herbal bite. Lone Pint didn’t rush this one to market. They brewed it until it felt right, and that patience paid off.

Live Oak Hefeweizen – Live Oak Brewing Company (Austin)

This traditional German wheat beer honors the old-world style with exacting care. It offers notes of banana and clove from the yeast, balanced with a smooth, creamy body and gentle carbonation. Many consider it one of the best hefeweizens brewed in the United States, and it holds that title without flash or flair.

Hans’ Pils – Live Oak Brewing Company (Austin)

Crisp and hop-forward, this pilsner pulls from northern German inspiration. The bitterness hits early and clean, leaving behind a dry, satisfying finish. Hans’ Pils doesn’t aim to be trendy. It aims to be reliable, and it delivers with every pour.

Hopadillo – Karbach Brewing Company (Houston)

One of Karbach’s earliest successes, Hopadillo is an American IPA with solid bitterness, firm malt, and a classic West Coast structure. It helped push Karbach into broader markets and showed that Texas brewers could compete in hop-driven styles without chasing trends.

Best Maid Pickle Beer – Martin House Brewing Company (Fort Worth)

What began as a curiosity turned into a cult favorite. Brewed in collaboration with Best Maid Pickles, this sour beer is salty, tart, and unmistakably pickled. It may sound like a dare, but many drinkers come back for more. It’s a perfect example of Martin House’s willingness to take risks and lean into the unexpected.

Celis White – Celis Brewery (Austin)

Based on Pierre Celis’s original Belgian recipe, this witbier pours pale and cloudy with notes of orange peel, coriander, and soft wheat. It revived a nearly lost style in the U.S. and served as a reminder that brewing history still matters. Celis White blends European tradition with Austin creativity.

Shiner Premium – Spoetzl Brewery (Shiner)

Light, easy-drinking, and brewed with a sense of history, Shiner Premium sticks to what works. It doesn’t chase flash. It stays true to the Spoetzl legacy — approachable beer made with respect for the process and the people who drink it.

Why These Beers Matter

These beers didn’t all come from the same mold. Some broke rules. Others followed quiet traditions. What tied them together was purpose. Each one aimed to say something about Texas.

The Business and Legal Landscape

Texas runs on a three-tier system. Breweries, distributors, and retailers have to stay in separate lanes. This structure, set up after Prohibition, still affects how beer moves and who profits from it.

For years, brewers couldn’t sell their own beer directly to the people who came to try it. That slowed growth and added red tape.

Small Wins, Ongoing Work

By the 2010s, groups like the Texas Craft Brewers Guild helped push new laws across the finish line. Breweries could finally sell beer to-go and host taprooms with fewer limits. These changes didn’t fix everything, but they opened a path forward.

Even now, some counties keep dry laws in place. Big distributors still shape what gets on shelves. Small brewers have to navigate this landscape daily.

Beyond Brewing

Running a brewery in Texas takes more than grain and hops. It takes time at the Capitol, conversations with lawmakers, and a steady push against old structures. Brewery owners don’t just brew — they advocate. They write policy proposals, attend city council meetings, and stay involved with groups like the Texas Craft Brewers Guild, which has become a central voice in policy efforts.

Many of these brewers spend as much time reviewing legislation as they do refining recipes. They track bills that could limit direct sales, restrict taproom hours, or add new fees. Some testify at public hearings. Others organize petitions or meet with local representatives to explain how small changes in law can either help a brewery grow or force it to pull back.

Beer and Texas Identity

Beer shows up everywhere in Texas. At fish fries, tailgates, and county fairs. In coolers at deer leases and tucked into saddle bags on long trail rides. It’s passed around folding chairs, poured from pitchers in small-town diners, and bought in corner stores where folks still pay in cash. Some people crack open a cold one in the exact same spot their parents did, without thinking twice about it.

In small towns, beer means comfort. A familiar label, a trusted taste, something you can count on. In cities, it becomes a way to explore. A chance to try something new, to talk about what’s in the glass and where it came from. The background may change, but beer never seems to go far.

Something Deeper

People may not call it tradition, but it carries the weight of one. Beer becomes part of the rhythm — a steady presence that fits into quiet evenings, loud get-togethers, and everything in between. It’s not flashy. It’s reliable.

For a lot of Texans, it feels like home in a bottle. Not because of marketing or a slogan, but because of what it brings to mind. A moment. A place. A person. That’s what sticks.

The Future of Texas Beer

New brewers keep coming to Texas. Some open second taprooms. Others stay small and focus on their neighborhood. There’s no single way to grow here. The shape depends on the place.

New Ideas, Familiar Intent

Styles are changing. Sours and low-alcohol beers are gaining ground. Non-alcoholic options are finding shelf space. Some breweries now work with Texas farmers to source fruit, grain, and herbs grown down the road.

None of this feels like a detour. It’s just another direction for brewers chasing what feels right for the people who drink their beer.

The Road Ahead

Rising costs and distribution challenges aren’t going away. Big brands still take up space. But Texas brewers know how to work through obstacles. They’ve been doing that since day one.

Conclusion

Beer in Texas didn’t spring up all at once. It took shape across miles and decades. Every era brought something different. People kept brewing, whether times were good or dry or uncertain.

The tools have changed. The flavor profiles look different. But the point hasn’t moved. Texans still make beer that feels like it belongs here.

And that story keeps pouring.