The Comanche people, originally a branch of the Northern Shoshone from the Great Basin region, transformed into a dominant force across Texas and the Southern Plains after acquiring horses in the late 17th century. This pivotal moment allowed them to develop a nomadic, horse-centered culture, excelling as riders and warriors. Their territory, known as the Comanchería, spanned present-day northwestern Texas and adjacent areas in New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and Oklahoma. This evolution from modest mountain dwellers to formidable Plains warriors showcases the Comanche’s adaptability and resilience.

Origins and Early Migration to the Great Plains

The Comanche trace their origins to the Northern Shoshone people of the Great Basin, living as hunter-gatherers before a pivotal transformation reshaped their way of life. The introduction of horses in the late 17th century revolutionized their mobility, enabling them to develop an equestrian-based culture centered around hunting and warfare.

This shift allowed the Comanche to expand southward onto the Southern Plains, where they became dominant by the 18th century. As they moved into Texas, they displaced the Apache and established control over a vast region known as the Comanchería. Over time, the tribe divided into several bands, with five major divisions emerging to govern different parts of their extensive territory. Unlike the ceremonial mounds builders who preceded them in Texas, the Comanche developed a more mobile culture centered around following bison herds.

The Transformative Power of the Horse Culture

The arrival of the horse transformed Comanche society, turning them into one of the most powerful mounted forces on the Great Plains. This shift enabled them to expand rapidly, outmaneuvering both Native and European adversaries with their superior cavalry skills.

Horses also revolutionized their economy, allowing for more efficient bison hunting across vast territories. The Comanche’s wealth and status came to be measured in horses, with elite members sometimes owning over 100. Beyond warfare and hunting, horses improved daily life by enabling the transport of larger homes and greater supplies, replacing the limited capacity of their earlier dog-drawn travois system.

This adaptation made the Comanche one of the most influential and mobile tribes in North America. Like the Apache buffalo hunters, they utilized every part of the bison for their survival, creating tools, shelter, and sustenance from their kills.

Life, Society, and Cultural Practices

Nomadic life influenced every aspect of Comanche society, from their spiritual practices to their daily routines. Their belief systems were deeply connected to their mastery of horses and reliance on buffalo, reflecting a way of life centered on mobility and survival across the plains.

Child-rearing mirrored their warrior culture, with boys learning hunting and combat skills from an early age. By their teenage years, they were skilled horsemen and warriors, prepared to defend and sustain their community.

Women played essential roles, particularly in childbirth, where experienced midwives assisted in specialized dwellings. Their contributions extended to processing hides, preparing food, and ensuring the tribe’s mobility.

Practicality defined Comanche clothing. Men typically wore breechcloths and leggings, while women dressed in buckskin garments and moccasins, often adorned with porcupine quills and animal fur. Warriors maintained a distinctive look, wearing their hair in two braids with a decorated scalp lock at the crown, a symbol of their status and identity.

Warriors of the Southern Plains

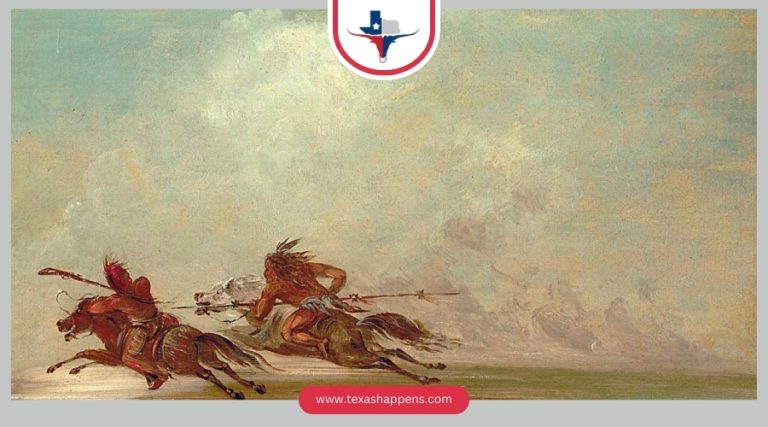

Renowned for their mastery of mounted warfare, Comanche warriors were among the most formidable fighters on the Great Plains. From childhood, they trained in hunting and combat, developing skills that made them highly effective raiders, capable of striking with unmatched speed and precision.

Their expertise in horseback combat allowed them to blend traditional weapons, such as bows and lances, with firearms acquired through trade. This adaptability enabled them to launch strategic raids on Spanish, Mexican, and American settlements, asserting their dominance across the Southern Plains for over two centuries.

However, their power began to wane in the late 1800s as U.S. military campaigns intensified and the destruction of buffalo herds—central to their way of life—left them vulnerable. These combined pressures ultimately forced the Comanche to surrender and transition to life on reservations. Before the Battle of Medina in 1813, the Comanche controlled vast territories that extended into Spanish-held regions of Texas.

Relations with Spanish, Mexican, and American Settlers

Throughout their dominance over the Southern Plains, Comanche relations with settlers evolved from violent conflicts to complex diplomatic arrangements. Upon their arrival in North Texas, they forcibly displaced the Apache and asserted control over the region. Their power became clear in 1758, when they led a coalition attack that destroyed the Spanish Mission at San Sabá, escalating hostilities with Spain. Over time, however, Spain recognized the necessity of peace and engaged in trade-based diplomacy with the Comanche.

After Mexico gained independence, its weakened military presence in Texas resulted in increased conflicts between settlers and the Comanche. The Mexican Colonization Law of 1824, which encouraged American immigration, further strained relations as more settlers moved into Comanche territory.

Even after Texas won independence, policies toward the Comanche varied significantly. Sam Houston pursued diplomacy, often securing temporary peace, while Mirabeau B. Lamar launched aggressive military campaigns, leading to bloody confrontations like the Council House Fight and the Battle of Plum Creek (1840). Though these battles weakened the Comanche, their removal from Texas would not be complete until the U.S. military campaigns of the 1870s, which—combined with the destruction of the buffalo—ultimately forced them onto reservations.

The Rise and Dominance of Comancheria

After acquiring horses in the late 1600s, the Comanche transformed themselves into one of North America’s most dominant military powers. Their mastery of mounted warfare and strategic raiding enabled them to establish Comancheria, a vast domain stretching across modern-day Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Colorado, and Kansas.

Their economic influence grew as they controlled the trade of horses, weapons, and captives, engaging in both raiding and diplomacy with Spanish, Mexican, and American settlements. Their military power was so complete that they displaced the Apache from much of the Southern Plains and conducted raids deep into Mexico, extracting wealth and captives with little resistance.

For over two centuries, the Comanche remained the dominant force in the region. However, their reign came to an end in the late 19th century, as U.S. military campaigns and the mass extermination of buffalo devastated their way of life. By 1875, after prolonged resistance led by Quanah Parker, the remaining Comanche were forced onto reservations in Oklahoma, marking the end of their era of power on the Plains.

Wrapping Up

The Comanche left an enduring mark on Texas history, transforming from a modest offshoot of the Shoshone into one of the most dominant forces on the Southern Plains. Their mastery of horseback warfare, strategic raids, and vast trade networks shaped the region for over two centuries. While conflicts with settlers and the U.S. military eventually led to their forced relocation, the legacy of the Comanche remains deeply woven into the cultural fabric of Texas.

Today, the Comanche Nation continues to thrive, preserving its traditions while embracing modern economic and educational initiatives. Their resilience and adaptability stand as a testament to their enduring spirit, ensuring that their rich history is remembered and celebrated for generations to come.