A place where imagination and nature meet, Guadalupe Mountains National Park is a place where you can take in the awe-inspiring views of mountains and canyons as well as dunes and deserts in a setting that is truly unique. National Park Guadalupe Mountains has the world’s largest Permian fossil reef and the four highest peaks in Texas, an ecologically diversified assemblage of flora and wildlife, the story of lives shaped by conflict, cooperation, and survival.

The Geological Background

Permian Period, or the last Paleozoic era, which occurred 251 to 299 million years ago, caused Guadalupe Peak to rise to its current height from being an ocean floor. Since time immemorial, the earth’s surface has likewise changed and transformed. Plates of crust moving over softer material constantly shifted the position of the continents. A reef surrounded the Delaware Sea in the middle of the Permian Period. The Capitan Reef, now known as one of the best-preserved fossil reefs on earth, flourished and prospered around the Delaware Basin margin for many million years before environmental factors that were vital to its expansion were altered around 260 million years ago.

The Delaware Sea began to dry up because the exit from the Permian Basin to the ocean was constrained. Mineral salts and dirt began to create thin, alternating bands on the seafloor as minerals precipitated from the receding waves. These narrow bands entirely covered the reef for tens of thousands of years. Tectonic compression along the western coast of North America around 80 million years ago caused the area comprising west Texas and southern New Mexico to rise steadily. The creation of steep faults on the western edge of the Delaware Basin was triggered by a change in tectonic events 20-30 million years ago. A long-buried section of the Capitan Reef rose several thousand feet beyond its original position because of movement on these faults over the previous 20 million years. Wind and rain eroded the soft top strata, exposing the harder-to-erode fossil reef beneath and resulting in the present-day Guadalupe Mountains.

Rich Historical and Cultural Background

For more than 10,000 years, the Guadalupes Mountains have witnessed a steady stream of human history, including brutal wars between Mescalero Apaches and Buffalo Soldiers, the transit of the Butterfield Overland Mail, and the arrival of ranchers and settlers, and finally, the creation of a national park. Historical landmarks, including Frijole and Williams Ranches, along with the Pinery Station’s crumbling remains, have been conserved for future generations.

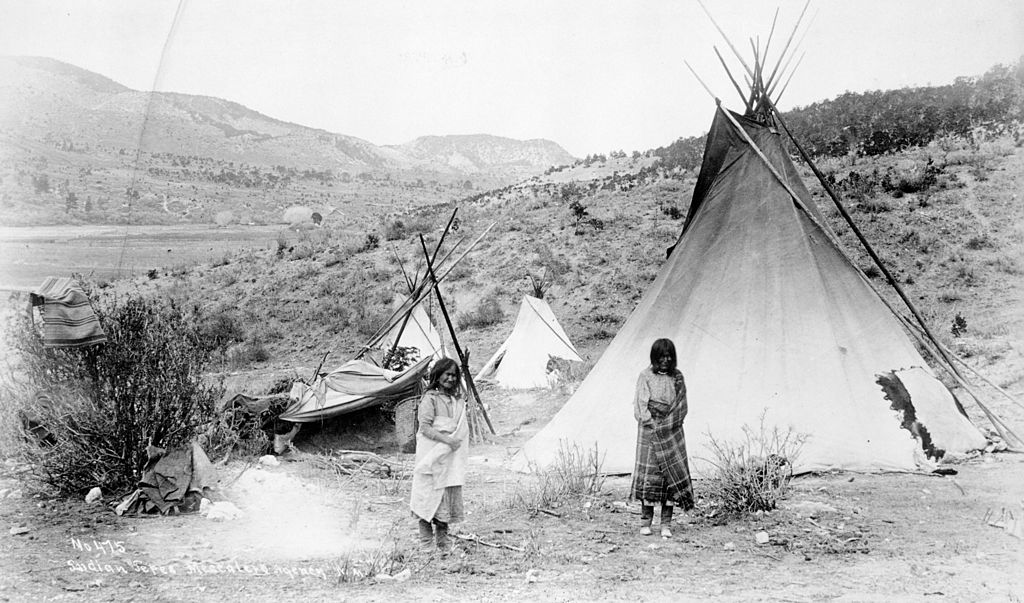

The Guadalupe Mountains served as the last refuge for the Mescalero Apaches when driven to flee the plains by the Comanches, who had waged war against them. They make a living by utilizing the local flora and fauna. Throughout their long history, the Mescaleros have been on the move, traveling huge distances and following the seasons. It was not until settlers began moving into the area quickly that the Mescaleros were forced to adapt to the severe conditions they had to live under. They were suddenly robbed of their abundance of resources and vital water sources. The Mescalero Apaches attempted to defend their territory by raiding and attacking stages and villages, but soldiers and cavalrymen destroyed them in terrible skirmishes. The Mescaleros were primarily expelled from the Guadalupes by the late 1800s. The Guadalupe Mountains remain a sacred site for the Mescalero Apache people today. For ritual purposes, members of the tribe visit the area each year to collect agaves.

Archaeological evidence, such as projectile points, baskets, pottery, and rock art, dates the first inhabitants of Guadalupes to over 10,000 years ago. Since then, various groups have come and gone, including the Spanish in the 1500s. Even after the Mescaleros were expelled, permanent settlements in the Guadalupes remained rare. In less than a year, the Butterfield stage route across the Guadalupes was abandoned for a southern way via army forts. Most settlers found the range inhospitable.

The park was proposed in 1923, but Wallace Pratt made it a reality. Pratt was a geologist with the then-small Humble Oil and Refining Company. In 1921, attracted by McKittrick Canyon’s geology and beauty, he began buying acreage there. Pratt erected the Pratt Cabin at the confluence of the north and south McKittrick canyons and Ship-On-The-Desert near the canyon mouth. McKittrick Canyon, which he donated, formed the core of Guadalupe Mountains National Park. The government bought 80,000 acres from J.C. Hunter Jr. The land transfer was complete by 1970 when Congress passed the appropriate legislation. Guadalupe Mountains National Park opened in 1972.

What Awaits You at Guadalupe Mountains National Park

a. Biological Diversity

Guadalupe Mountains National Park has around 1000 plant species. Many are familiar desert species like ocotillo and prickly pear, but others are unique to the park. Steep-walled canyons, high-country ridge tops, wide-open desert lowlands, and lush riparian oases provide unique and varied living zones spanning thousands of acres with over 5000′ of elevation variation.

The Guadalupe Mountains constitute a diverse island in the desert. The park has several ecozones. These include the harsh Chihuahuan desert, streamside oak, maple woodlands, steep gorges, ponderosa pine, and Douglas fir mountainside forests. It is home to 60 mammalian species, 289 avian, and 55 reptile species. The park’s main predators are coyote bobcats, gray foxes, badgers, black bears, gold eagles, and peregrine falcons. The javelina, elk, skunk, mule deer, woodpecker, great horned owl, and the prominence roadrunner are some other popular wildlife species. The desert may appear lifeless, but it supports an astounding variety of fauna.

b. A Terrain of Hiking Trails

Eighty miles of trails lead you through desert vegetation, gorges, and riparian oases, while long, strenuous hikes will carry you into the high country forest or to the “Top of Texas.” The enchantment of Guadalupe Mountains National Park is just around the bend.

1. Devil’s Hall.

Devil’s Hall Trail is 3.8 kilometers round-trip from Pine Springs Trailhead. After a mile, the trail enters a rough wash that leads to a natural rock stairway and canyon “hallway.”

2. Loop Smith.

The 2.3-mile Smith Spring Trail begins at Frijole Ranch Trailhead. Loop through desert scrub and riparian vegetation.

3. McKittrick Canyon Trail.

Follow the trail through riparian vegetation and stream crossings to Pratt Cabin or Grotto. McKittrick Canyon is an average hike that follows the canyon bottom and climbs 3 miles to McKittrick Ridge.

4. Guadalupe Peak Trail.

Guadalupe Peak is 8.5 km round-trip and climbs 3,000 feet through a conifer forest, one of the most notable hiking destinations in Texas The strenuous ascent is rewarded by West and South views. Allow 6-8 hours of trailing and bring a drink, sun protection, and nourishment.

5. El Capitana.

El Capitan is a breathtaking mountain, one of the world’s most recognizable mountains; it seems more like an eroded rock placed on top of a hill. The peak’s elevation is 2,464 feet making it Texas’ 10th tallest mountain.

As Texas’s tallest peak, Guadalupe Peak State Park offers breathtaking views, calm forest trails, fascinating local history, and the world’s largest Permian fossil reef. Explore dunes, gorges, and mountains in Guadalupe Mountains National Park and the park’s varied flora and animals. People often point to the region’s rough and rocky topography as the region’s most notable feature when discussing the region’s natural attractions. Nearly a solid desert wall can be seen from the roadway as it winds through the mountains. When you travel through one of the national park’s entrances, even a short walk, you’ll be surprised by the beauty of the canyons and the abundance of wildlife and birds.