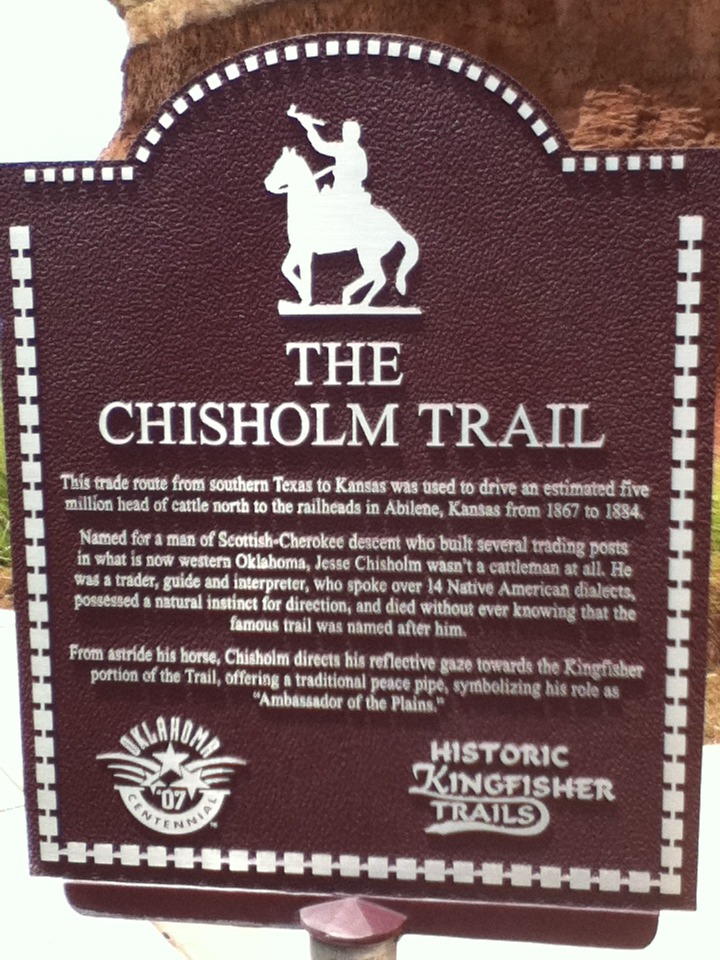

Step into the period of the Chisholm Trail, an iconic route that transformed Texas’s economy by moving over five million cattle to Kansas from 1867 to 1884. Jesse Chisholm established this pathway in 1864, sparking an economic revolution by meeting Northern beef demands. The drive required skilled cowboys managing herds, covering ten to twelve miles daily. Abilene, Kansas, boomed as a key cattle market thanks to the trail. Although barbed wire and quarantine laws ended its use by 1884, its legacy remains vivid in American folklore and media. Uncover the rich history and enduring impact of this legendary cattle trail.

Historical Importance

The historical significance of the Chisholm Trail lies in its transformative impact on the American livestock industry and economy. From 1867 to 1884, this trail became a crucial artery for moving over five million cattle from South Texas to Kansas. With cattle breeds like Longhorns leading the way, the Trail revitalized Texas’s post-Civil War economy and met Northern markets’ beef demands. Jesse Chisholm, initially marking the trail in 1864 for trade, unknowingly set the stage for an economic revolution. As you investigate this historic path, you’ll find trail markers that tell stories of cowboys and the rugged expeditions they undertook.

At the heart of the trail’s significance was Abilene, Kansas, established by Joseph G. McCoy as a major cattle market. In its initial year, 35,000 cattle marched into Abilene, turning it into a vibrant hub. This movement didn’t just enhance economies; it solidified the cultural identity of the American cowboy, becoming an emblem of the Old West. However, by the late 1880s, railroads and quarantine laws began to overshadow this iconic route, marking the end of a period but forever changing the cattle industry.

Trail Development

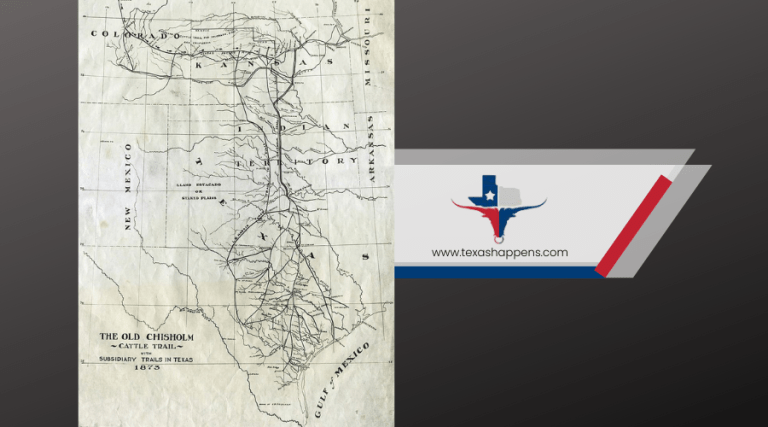

Starting with Jesse Chisholm’s trade routes marked in 1864, the Chisholm Trail quickly developed into a crucial pathway for cattle drives from southern Texas to Kansas railheads. By 1867, the initial cattle drive along this trail took place, adopting the path Chisholm had established. As you examine the history of this trail, you’ll find that its markings became a significant guide for the drovers who followed. The trail’s popularity surged, and soon, it was known by multiple names, including the Kansas Trail and the Abilene Cattle Trail.

The trail’s development wasn’t static; it adapted over time to meet the needs of the cattle industry. As new markets emerged, route variations became a common feature. Different paths were established to lead cattle to key railheads in Kansas, ensuring that the trail evolved alongside the growing demands of cattle transport. Publications from as early as 1870 referenced these noteworthy routes, highlighting their significance in the cattle trade.

However, by 1884, the trail’s usage declined due to barbed wire and quarantine laws. These changes restricted cattle movement, confining the trail’s activity primarily to areas like Caldwell, Kansas, marking the end of a period.

Cattle Drive Techniques

As the Chisholm Trail evolved to meet the demands of the cattle industry, mastering cattle drive techniques became critical for the success of every expedition. Effective herd management was imperative, and you’d find cattle driven in loose formations. This approach minimized the risk of stampedes and allowed the cattle to graze along the route, a fundamental grazing strategy for maintaining their health. Covering an average of ten to twelve miles each day, locating water sources was a priority to keep the herds hydrated.

Working as a well-oiled machine, the team consisted of trail bosses, cowboys, cooks, and horse wranglers. Each cowboy had a designated role—whether at the point, flanking, or dragging—to maintain order and direction. These positions were key to managing the herd’s pace and direction effectively.

Night hawks played a vital role, keeping watch to prevent stampedes and protect the herd from threats under the cover of darkness. This vigilance was essential for the cattle’s safety.

Ultimately, trailing cattle was a cost-effective solution, averaging just sixty to seventy-five cents per head, markedly cheaper than rail transport. This affordability made the Chisholm Trail a preferred option for ranchers.

Economic Influence

Undeniably, the Chisholm Trail reshaped the post-Civil War Texas economy by driving millions of cattle to northern markets, where prices soared from $2 per head in Texas to over $16. This remarkable price increase provided a lucrative opportunity for ranchers, leading to the rapid growth of the cattle market. One crucial player, Joseph G. McCoy, established Abilene, Kansas, as a central hub in 1867, transforming it into a lively cattle market, with 35,000 cattle arriving in the initial year alone.

The trail’s success attracted Eastern and foreign investors, who poured funds into the establishment of expansive ranches across the Great Plains. These investments greatly altered Texas’s ranching landscape, spurring the formation of ranching partnerships. Notable collaborations, such as that between Charles Goodnight and John Adair, emerged to capitalize on the booming industry.

Moreover, the introduction of trailing contractors radically changed herd management. Ranchers could now efficiently drive large herds at a fraction of the cost, spending only sixty to seventy-five cents per head compared to expensive rail transport. This economic efficiency further solidified Texas’s role in the national cattle market, driving widespread prosperity across the region.

Closure and Legacy

While the Chisholm Trail’s economic impact was transformative, its operational days eventually came to an end. By 1884, the trail officially closed due to two major developments: the widespread use of barbed wire and the implementation of quarantine laws. These innovations restricted cattle movement, signifying a shift from traditional cattle drives to more structured ranching practices. The trail once teemed with life, moving an estimated five million cattle from 1867 to 1884. However, by its final year, cattle drives had dwindled, only reaching as far north as Caldwell, Kansas. This marked the end of an age and the dawn of the ranching evolution.

The Chisholm Trail’s closure symbolized more than just the end of cattle drives; it represented a significant transformation in American agriculture and economy. Railroads became the primary method for transporting cattle, making the trail’s legacy a reflection of change and adaptation. Today, the Chisholm Trail remains a powerful symbol of the cowboy period, reflecting:

- Trail symbolism of the Great Plains’ transformation.

- The shift to more structured ranching evolution practices.

- The end of open-range practices and the rise of modern ranching.

- The enduring influence on American culture and history.

Kiddo27, Chisholm Trail Historical Marker Kingfisher, CC BY-SA 3.0

Cultural Impact

The Chisholm Trail‘s cultural impact echoes through American media and folklore, vividly shaping our perception of the Old West. You’ve probably seen its influence in film representations like “The Old Chisholm Trail” (1942) and “Red River” (1948), which romanticize the cowboy life and thrilling cattle drives. These films helped cement the cowboy archetype in popular culture, portraying cowboys as rugged, adventurous figures traversing the untamed West.

TV series like “Rawhide” and the miniseries “Lonesome Dove” further spotlight the Chisholm Trail’s significance. They depict the challenges and adventures of trail driving, bringing the narrative of the Old West to life. These stories, enriched by personal accounts from trail drivers such as Teddy Blue Abbott and Andy Adams, give you a glimpse into the real experiences and hardships faced by those who braved the trail.

The legacy of the Chisholm Trail also lives on in Texas heritage trails, celebrating its historical importance and cultural impact on Texas identity. Through media, the trail has solidified the connection between Texas longhorns and the cowboy archetype, contributing to the broader cultural narrative of the American West.