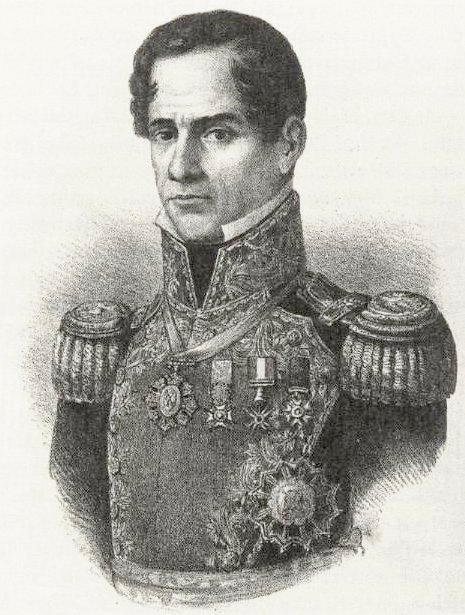

The Battle of the Alamo was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution, lasting for 13 days from February 23 to March 6, 1836, in San Antonio, Texas. It culminated in a decisive victory for Mexican forces under the command of President General Antonio López de Santa Anna, who reclaimed the Alamo Mission and killed most of the Texians and Tejanos inside.

Despite the defeat, the Battle of the Alamo became a symbol of fierce resistance and inspired many to join the Texian army in pursuit of revenge. The battle cry “Remember the Alamo!” echoed during the Mexican-American War, embodying the spirit of the Texan fight for independence.

Background

In 1835, Mexico, which then owned Texas, experienced a significant shift in governance. The triumph of conservative forces led to new constitutional changes that fundamentally altered Mexico’s organizational structure, ending the first federal period and establishing a centralized unitary republic. These changes, formalized by President Antonio López de Santa Anna in December 1835, aimed to centralize and strengthen the national government.

The new policies, including increased enforcement of immigration laws and import tariffs, sparked unrest among immigrants in Mexican Texas, many of whom were from the United States and living there illegally. Accustomed to a federalist government with extensive individual rights, these settlers were vocal in their opposition to Mexico’s shift toward centralism.

Mexican authorities, already suspicious of American immigrants due to previous U.S. attempts to acquire Mexican Texas, blamed much of the Texian unrest on these settlers. The immigrants, who made little effort to adapt to Mexican culture and continued to practice slavery despite its abolition in Mexico, further fueled tensions.

In October 1835, Texians engaged Mexican troops in the first battle of the Texas Revolution. In response, Santa Anna assembled a large force to restore order, consisting mostly of raw recruits, many of whom were conscripted.

Despite their inexperience, Texian forces systematically defeated the Mexican troops stationed in Texas, primarily composed of recent arrivals from the U.S. This success infuriated Santa Anna, who saw it as U.S. interference in Mexican affairs. He spearheaded a resolution classifying foreign immigrants fighting in Texas as pirates, ordering their immediate execution if captured.

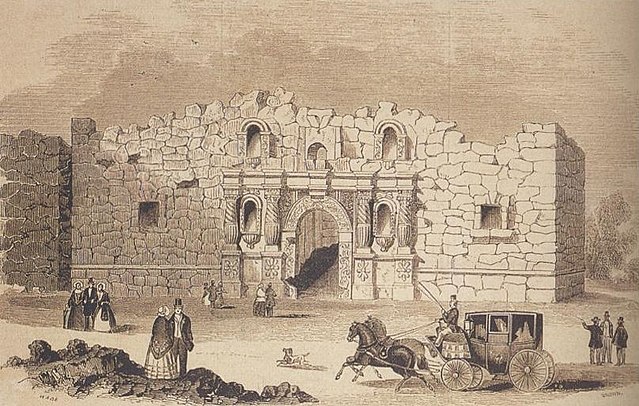

When Mexican troops withdrew from San Antonio de Béxar (now San Antonio, Texas), Texian soldiers captured the Mexican garrison at the Alamo Mission, a former Spanish religious outpost converted into a makeshift fort by the recently expelled Mexican Army.

The Lead-Up to the Battle

By December 1835, a series of Texian victories had driven Mexican federal forces south of the Rio Grande. However, the success was short-lived. Santa Anna’s Mexican army advanced north to crush the rebellion, while most of the victorious Texian volunteer army disbanded and returned home. Small garrisons remained in several towns, including San Antonio, where the Texans occupied the Alamo.

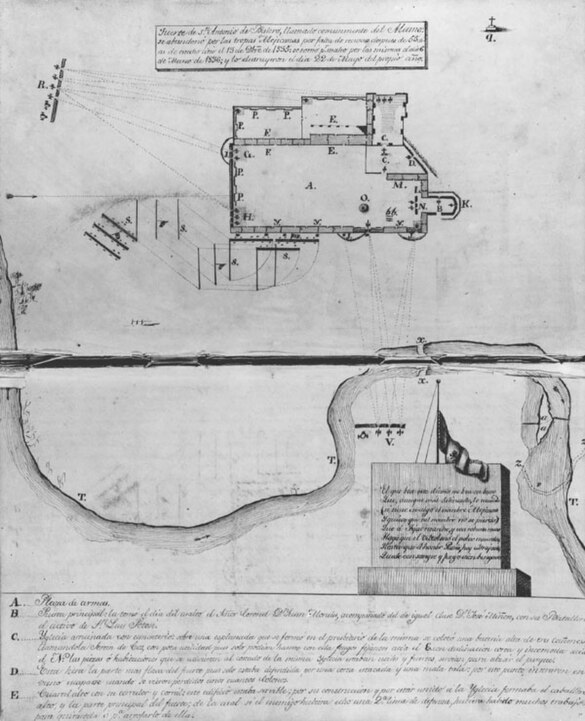

The Alamo, consisting of three one-story adobe buildings with log palisades enclosing open plaza areas, was armed with 19 cannons along its walls. In December 1835, a group of Texian volunteers led by George Collinsworth and Benjamin Milam overwhelmed the Mexican garrison at the Alamo, seizing control of San Antonio.

By mid-February 1836, Lieutenant Colonel William B. Travis and Colonel James Bowie had taken command of the Texian forces in San Antonio. Despite Commander-in-Chief Sam Houston’s recommendation to abandon the town due to insufficient troops, Travis and Bowie fortified their position at the Alamo. Reinforcements were scarce, and their numbers never exceeded 200.

The Siege and Battle of the Alamo

On February 23, 1836, Santa Anna arrived with his advance detachment and demanded the Alamo’s unconditional surrender. The Texians responded with a cannon shot, signaling their refusal. Enraged, Santa Anna ordered that no quarter be given, and a 13-day siege began.

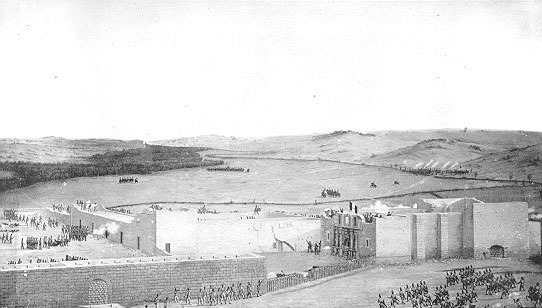

The Mexican force, numbering between 1,800 and 6,000 troops, besieged the fort, setting up artillery opposite the south and east walls. A steady bombardment ensued, with cannonballs being exchanged until the Texians were ordered to conserve their limited powder. Santa Anna’s troops gradually moved closer to the Alamo but remained outside the range of the Texians’ rifled muskets.

The cold winter weather made the battle challenging for both sides. Despite two small groups of Texian reinforcements breaking through the Mexican lines, Santa Anna’s forces continued to grow. On March 3, the last element of Santa Anna’s army arrived, and he prepared for a full-scale assault.

The Final Assault

Before dawn on March 6, 1836, four columns of Mexican infantry attacked the Alamo from different directions. The defenders, forced to expose themselves to fire over the walls due to the lack of firing ports, used cannons loaded with nails, horseshoes, and scrap iron to repel the Mexican forces. The first assault was repelled with rifle fire, but the Mexican infantry regrouped and launched another attack.

During the battle, Travis was killed while opposing a mass attack against the north wall, which was eventually breached. As the Mexican troops advanced, they turned a cannon covering the south wall against the defenders, allowing Mexican forces to overrun that section.

The Texian defenders retreated to the barracks buildings, where they engaged in fierce room-to-room combat. Bowie, who had been ill, was killed during the battle. Outside the walls, two groups of Texians attempting to escape were cut down by Mexican cavalry. The final stand occurred in the chapel, where a small Texian detachment fired their last cannon before being overrun in hand-to-hand combat.

Aftermath and Legacy

Nearly all the Texian defenders were killed during the battle, with Mexican forces suffering heavy casualties, losing between 600 and 1,600 men. Texian families sheltered at the Alamo were spared, but surviving fighters were executed on Santa Anna’s orders.

The Battle of the Alamo, though a defeat for the Texians, became a rallying cry for the Texas Revolution and later the Mexican-American War. The sacrifice of the defenders inspired many to join the Texian army, leading to eventual victory at the Battle of San Jacinto and the establishment of the Republic of Texas.