The Coahuiltecan peoples once called the brush-covered plains of South Texas their home—small, mobile bands of hunter-gatherers who adapted to harsh terrain, linked across missions, rivers and the Rio Grande corridor. Their story reminds us of endurance, adaptation and cultural change on the Texas frontier.

Origins of the Name and Identity

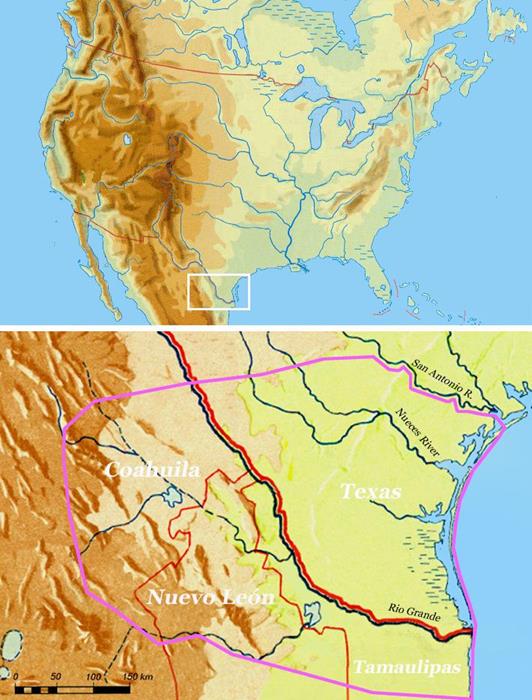

The term “Coahuiltecan” was coined by Spanish colonists to describe dozens—if not hundreds—of small Indigenous bands living in what is now southern Texas and northeastern Mexico (around Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas).

Modern scholars note that it’s more of a geographic/cultural catch-all rather than a single unified tribe: the Coahuiltecans spoke many languages, had varied ways of life, and no overarching political structure.

Where They Lived in Texas

The Coahuiltecan homeland stretched from the Rio Grande Valley, across the South Texas Plains, and toward the gulf-coast brushlands, bounded roughly by the Guadalupe River to San Antonio and westward toward Del Rio.

In this semi-arid land of mesquite, nopales and thorny brush, these peoples built a way of life suited to minimal resources and seasonal rhythms.

Life on the South Texas Plains

Rather than large villages or farms, Coahuiltecan bands were typically small, mobile groups that followed seasonal rounds, gathered plants, hunted small game and adapted to shifting food-resources.

Important staples included prickly pear (tunas and pads), mesquite beans (ground into flour), maguey and sotol crowns, pecans and a variety of animals like deer, rabbits, even armadillo and snails.

Their camps were often simple: brush shelters, small dwellings that could be set up or moved as needed.

Bands, Languages and Social Structure

Rather than one large polity, the Coahuiltecan region was made up of many bands—often 100–500 people—whose names show up in Spanish journals and mission registers. In and around present-day San Antonio, for example, records mention Payaya, Pampopa, Pacuache, Pajalate, and Xarame among others.

Linguistically, the picture is complex. The umbrella term “Coahuiltecan languages” covers several poorly documented tongues—some likely isolates, some possibly related (e.g., Comecrudo/Garza/Mamulique sometimes grouped as “Comecrudan” or “Pakawan” by different scholars). Because most languages survive only as short wordlists collected in the 1700s–1800s, modern linguists disagree on how (or whether) to classify them together.

Leadership tended to be local. Extended families linked into bands led by respected headmen (whom Spaniards often called capitán). Decisions were largely communal and pragmatic, shaped by season, water, and food availability.

Bands might split or fuse depending on the prickly-pear harvest, mesquite bean crop, or hunting prospects, then reconvene at favored water sources along rivers like the San Antonio, Guadalupe, or Nueces. This small-scale, mobile structure helped people survive in the semi-arid South Texas Plains.

Intermarriage and visiting ties stitched the social map together. As missions grew in the 1700s, registers show multiple bands arriving, marrying, or godparenting across mission communities—an archival clue to how multilingual networks operated even as populations declined. Xarame entries, for instance, appear across Mission Valero (the Alamo) and Mission Concepción.

Spiritual Traditions and Collective Life

Although less is recorded than for larger Plains nations, Spanish accounts and later ethnography describe multi-band mitote gatherings—nightlong dances with singing, drumming, and feasting—that doubled as diplomacy, matchmaking, and news exchange.

In parts of South Texas and northern Mexico, peyote figured into ritual contexts, embedded in a broader seasonal round that also included first-fruit observances tied to the prickly-pear and mesquite harvests.

These assemblies weren’t only about religion; they were how scattered communities renewed alliances, arranged marriages, traded goods (meat, hides, salt, plant foods), and coordinated movements before dispersing again to small brush-hut camps. Mission-era sources note that, even after relocation, people maintained distinct dialects and practices, which hints at the resilience of these collective rites under colonial pressure.

First Encounters with Europeans

One of the earliest European contact moments came when Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca wandered through what is now Texas in the 1530s; his accounts include Indigenous peoples around the region later identified as Coahuiltecan.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Spanish missions and presidios expanded into the region—for example the establishment of Mission San Antonio de Valero (later the Alamo) in 1718 brought missionization into the lands of Coahuiltecan bands.

Mission Life, Disease and Displacement

As Spanish settlement advanced, many Coahuiltecan bands were drawn or pushed into mission life. The introduction of European diseases like smallpox and measles, combined with competition for resources and slave-raiding, caused dramatic decline.

By the mid-18th century, the Coahuiltecan region had undergone major transformation: many bands assimilated into mission communities, lost distinct identity, or were absorbed into other groups.

Legacy and Cultural Survival

Though the Coahuiltecan peoples are often described as “extinct” as distinct tribes by the 19th century, their legacy lives on in South Texas through archaeology, place-names and descendant communities.

For example, the Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation (based around San Antonio) is comprised of Coahuiltecan descendants working to preserve heritage, language and traditions.

Visitors to San Antonio can also engage with the historic missions, think about the original Indigenous inhabitants of the region, and reflect on the depth of Indigenous presence before statehood.

Why the Coahuiltecan Matter in Texas History

The Coahuiltecan story is less often told than that of larger Plains nations, but it is crucial for understanding the South Texas frontier—a place of adaptation, cultural resilience, and change. Their ability to survive for thousands of years in a challenging environment, engage with Spanish missions, and persist culturally (even if transformed) adds depth to Texas’s Indigenous past.

When we traverse South Texas or visit historic missions near San Antonio, we walk upon lands once lived by Coahuiltecan bands whose stories still shape the place.