Imagine the vast South Texas brush country and rolling hills of the Edwards Plateau echoing with the thunder of horse hooves, as a community of fierce horse-riding, desert-savvy warriors and hunters carved out a place for themselves long before modern highways and ranch fences. That was the Lipan Apache — known in their own tongue as Łepai-Ndé, the “Light-Gray People.”

Their story is one of mobility, survival, shifting alliances, and adaptation across the ever-changing frontier of Texas and northern Mexico. Here’s a journey through key chapters of their history, culture, and legacy.

Homeland and Range in Texas

The Lipan Apache traditionally ranged across a broad swath of territory: south and west Texas, north into present-day Oklahoma and Colorado, and into the northern Mexican states of Coahuila, Chihuahua and beyond.

In Texas they traveled and lived across the Edwards Plateau, the brush country of South Texas, the Big Bend borderlands and the lower Río Grande region. Their ability to navigate rugged terrain and adapt to both plains and desert made them formidable.

Origins and Identity

The Lipan Apache are part of the Southern Athabaskan (Apache) family of peoples. Their self-designation, Łepai-Ndé (or Lépai-Ndé) translates roughly to “the Light-Gray People.”

Over time the Lipan developed a distinct identity shaped by mobility, horse culture, hunting, raiding, trade and navigating the complex frontier of Spanish, Mexican and American expansion in Texas.

Lifeways: Mobility, Foodways and Material Culture

Unlike many sedentary tribes, the Lipan were renowned for their mobility. They combined hunting (especially of deer and bison when accessible), gathering (mesquite, agave, cactus), horsemanship and occasional trade or raiding.

Using wickiups or simple mobile shelters, they adapted to changing seasons and threats. With the arrival of the horse (from the Spanish) they became even more mobile and powerful. Some scholars note they were among the earliest to adopt horse culture in their region.

Their material culture included Apache-style tools, hunting gear, and garments suited for brush, plains and desert terrain. Their food-gathering included both wild goods and trade for goods such as bison hides, horses and goods from settlements.

Neighbors, Trade and Alliances

The Lipan Apache did not live in isolation. They interacted with many neighboring peoples: Tonkawa, Comanche, Caddo, and other Apache bands. Their alliances shifted—sometimes they allied with Texan settlers or the Republic of Texas against common enemies like the Comanche.

They also participated in trade networks, including stock raids across the borderlands, horse trading, and involvement in European-colonial frontier conflicts. These interconnections shape much of the Lipan story.

Early Contacts and Spanish Missions

Their first recorded European contact falls in the Spanish colonial era. They were mentioned in Spanish records by the early 18th century, often in the context of raids or frontier conflict—though they had existed in the lands much earlier.

Spanish missionaries attempted to bring them into mission life (for example near the San Sabá River), but Lipan involvement was inconsistent, often due to their mobility and resistance to being tied to missions.

The Spanish viewed the Lipan as one of the major threats to the frontier of New Spain because of their mobility, raiding capability and geographical reach into Texas.

Conflict, Adaptation & the 19th Century

The 19th century brought enormous change. The Lipan were drawn into the conflicts of the Republic of Texas, the State of Texas, the US Army, and Mexican forces. They sometimes served as scouts allied with Texas forces.

They faced pressure from Comanche expansion, U.S. military and Mexican military campaigns, disease, loss of land, and shifting frontier boundaries. By the mid- to late-1800s their community numbers declined sharply: by about 1875 there were only approximately 300 Lipan in scattered bands in Texas and northern Mexico.

Some bands fled into Mexico or merged with other Apache groups, such as the Mescalero, while others were forcibly removed or displaced.

Society and Leadership

Lipan bands were organized around kin groups and war-bands, led by chiefs (or war-leaders) and headmen rather than large centralized authority. Their decision-making often hinged on consensus within the band rather than formal hierarchical structures—typical of many Plains/Apache cultures.

Spiritual traditions included creation stories, ceremonies tied to nature and hunting cycles. For example, their own tribal website features “Our Sacred History: Vignettes of Lipan Past” including their creation story.

As mobility increased, their social structures adapted: leadership in war-bands, raids, hunting expeditions, and movements across borderlands required flexible organization.

What Happened to the Lipan Apache?

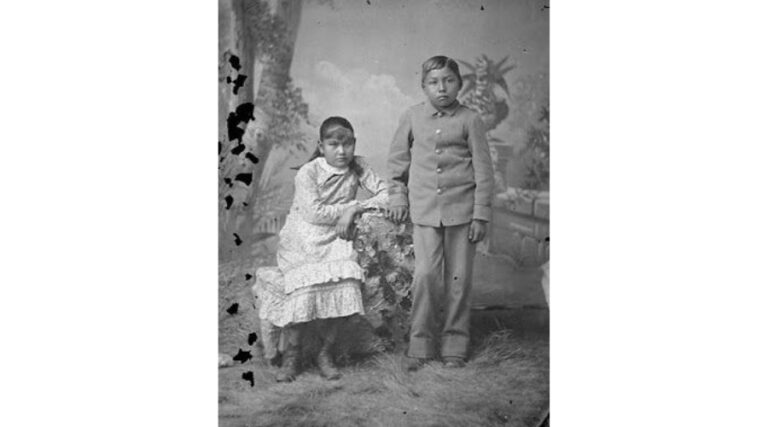

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries the Lipan Apache largely lost their autonomous territorial base in Texas. Military campaigns, smallpox and other epidemics, forced removal and assimilation, and resource loss took their toll.

Many Lipan were absorbed into other tribes, such as the Mescalero Apache or Tonkawa, while some descendants live in Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico and northern Mexico. They currently lack a single federally recognized tribe under the U.S. government (though several Lipan organizations exist).

Nonetheless, their legacy persists — through place-names, historical memory, and in living descendant communities who maintain cultural practices, pow-wows and language-revitalization efforts.

Legacy in Texas

The Lipan Apache’s presence in Texas spans centuries and landscapes—from hill country to brush, plains to borderlands. They challenged Spanish, Mexican and American frontiers and helped shape the history of the region.

Today their descendants and tribal organizations work to preserve Lipan heritage, ceremonies, language and culture. From the gravesites in West Texas and Coahuila to annual pow-wows in South Texas, their story is alive.

Understanding the Lipan Apache helps broaden the narrative of Texas: beyond the well-known Anglos and Mexicans, the Native peoples like the Lipan shaped the land and history in profound ways.

Conclusion

The Lipan Apache have been warriors, hunters, travelers, negotiators, survivors. Their story is one of movement and endurance across changing frontiers—of horses and plains, missions and removals, treaties and betrayals.

Yet the “Light-Gray People” remain, through memory, descendants and cultural revival. If you ever walk in the hills of the Edwards Plateau or the brush of South Texas, remember they were here long before roads and fences—and that their story continues today.