Chuck wagon food sustained cowboys on cattle drives with hearty basics like beans, salt pork, and sourdough biscuits. You’d find “Cookie” serving these meals from Charles Goodnight’s ingenious mobile kitchen, where strict mealtime etiquette governed every hungry cowhand. Today’s chuck wagon cook-offs honor these traditions with authentic cast-iron cooking techniques while adding modern twists. The influence of these trail meals extends far beyond the dusty cattle drives into America’s culinary identity.

The Birth and Evolution of the Chuck Wagon

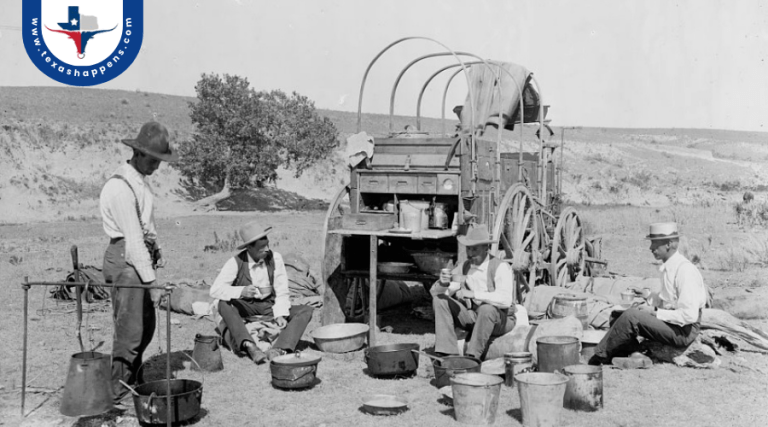

When cattleman Charles Goodnight repurposed a military surplus Studebaker wagon into a mobile kitchen in 1866, he couldn’t have known he was creating an icon of the American West. His innovation combined “chuck” (slang for food) with a practical wagon design, featuring a rear-mounted “boot” box with compartments for storing provisions and cooking utensils, plus a fold-down table for food preparation.

This mobile kitchen proved essential for long cattle drives across the frontier, where cowboys needed sustenance far from established settlements. The chuck wagon quickly became the heart of cowboy cooking operations in the Old West. As cattle drives expanded, so did the importance of these rugged kitchens. The design’s practicality allowed “Cookie” to efficiently feed hungry cowhands, making chuck wagons indispensable to the growing cattle industry.

During this period, these wagons played a crucial role in supporting the Manifest Destiny movement as cowboys helped expand American territories westward through their cattle drives.

Daily Fare: Staples and Protein on the Cattle Drive

Though lacking in variety, the chuck wagon diet provided cowboys with the essential fuel needed for their grueling work on the cattle drive. Beans formed the cornerstone of protein intake, often cooked in a Dutch oven alongside salt pork. Cowboys washed down their meals with strong coffee made by tossing crushed Arbuckle coffee beans directly into boiling water.

After long days on the open range, cowboys would gather for sourdough biscuits made simply with flour, water, and salt. The cook stored dried fruit in the chuck box—dried apples were particularly common. The basic fare was occasionally supplemented with freshly hunted game like deer or antelope, turned into stews. Hard cheese preserved in paraffin wax added welcome flavor to otherwise simple meals.

Much like how Texas oil boom transformed the state’s economy in the early 20th century, these humble trail foods would go on to influence Texan cuisine for generations.

The Role of “Cookie”: More Than Just a Camp Chef

While beans and biscuits sustained the crew, the man who prepared them held more power than outsiders might expect. As the trail boss’s right hand, Cookie managed more than just meals—he often performed veterinary tasks, minor medical care, gear repairs, and helped resolve disputes. His position held immense respect and authority.

The techniques used by these cooks were often influenced by the seasoned practices of Mexican vaqueros and earlier frontier traditions. No one ate until Cookie called for it—a rule that still governs many chuck wagon reenactments today.

Affectionately nicknamed “pot wrassler” or “bean wrangler,” Cookie was vital to the success of the drive. Cowboys valued their cook not only for nourishment but also for morale, recognizing that their health and spirits depended on what came from the chuck wagon.

Chuck Wagon Etiquette and Mealtime Traditions

Life on the trail followed strict unwritten rules, especially around mealtime. No one touched a plate until Cookie gave the go-ahead. Cowboys respected the chuck box area, avoiding dust, clutter, or disrespectful behavior near food supplies and equipment.

At outfits like the JA Ranch, a full plate was expected to be cleaned completely—wasting food was considered an insult. Cowboys who disrespected mealtime rules quickly earned a poor reputation.

While breakfast and supper were hot meals served from the wagon, lunch (or “dinner,” as it was often called) was typically eaten from the saddle—cold biscuits, jerky, or leftovers packed in bedrolls or saddlebags.

Trail hospitality was generous. Strangers or passing riders were routinely welcomed to the wagon—a legacy still honored today at public chuck wagon cook-offs and living history events.

From Trail to Table: The Modern Revival of Chuck Wagon Cuisine

Three key elements—tradition, flame, and iron—fuel today’s chuck wagon revival across the United States. If you’re craving fresh beef or cowboy beans prepared over an open flame, consider the growing popularity of cook-offs that recreate historical methods with modern ingredients.

In addition to beef, modern chuck wagon menus often include vegetables, spices, and artisan techniques that cowboys on the open range could only dream of. While cast-iron Dutch ovens and skillets remain the core cooking tools, today’s versions of chuck wagon chili or biscuits might feature brisket or even sour cream variations.

Traditional ingredients like flour, baking soda, beans, coffee, and dried fruit still show up, but now they mingle with gourmet updates—poblano-stuffed cornbread, peach cobbler with cinnamon glaze, and smoked tri-tip.

Competitions and heritage festivals across Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado celebrate this distinctly American food tradition, keeping cowboy cooking alive for new generations. Restaurants, ranches, and home cooks alike are embracing the rustic, hearty techniques of the chuck wagon kitchen—preserving the past one Dutch oven at a time.